- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Miharu

- Product Code: 4000-BD1808-15

- Weight: 120.00g

- Dimensions: 90.00in x 36.00in x 0.00in

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

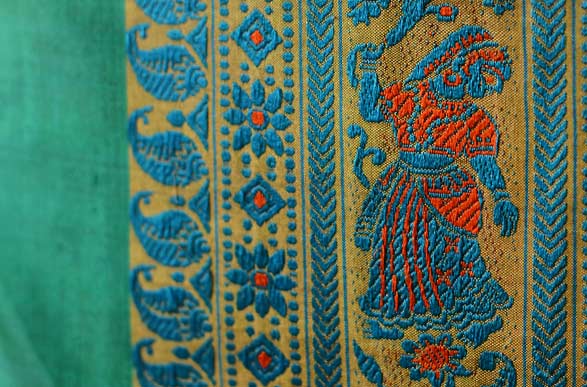

Mankind has always been inspired by images as visual references. Since the time we lived in caves a primal desire to depict surroundings and tell the tales of our life experiences has driven us to convert these images in tangible forms. With the advent of photography, the primitive techniques of preserving images are being overlooked, but there are art forms like Baluchari weaving which have kept the admirers swooning upon the meticulously planned arrangement of warp and wefts, depicting scenes from religious epics and courtly ceremonies as patterns on a piece of fabric. The Baluchari sarees of Bishnupur exude the motivation which propelled the artisans of Baluchar centuries ago to tell tales through their handwoven silk sarees.

The first Nawab of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan patronized this rich weaving tradition and brought this craft to Baluchar village of West Bengal. His encouragements made this art earn accolades worldwide and it flourished with the name of Baluchari weaving. In 18th century, during the reign of Murshid Khan European trade especially in textiles was on surge. From Bengal, large volumes of goods were exported to European ports. Silk and cotton were the highly sought after commodities.

The master weavers were provided with cultivable land and ponds by Nawabs in exchange of the exquisite weaves. In those times, when all the processes including cleaning & sorting of cotton, spinning, dying, planning the pattern, laying the warp and finally weaving were completely manual, a weaver family could only produce two to three saris in the whole year. Each sari was created with motifs based on a theme, the themes too revolved around the lives of Nawabs. A Nawab sitting on the throne and his nobles positioned at their respective places, A Nawab lying on his bed with a cup of wine, while a girl is dancing supported by the musicians are some popular scenes seen on these hand woven saris. The specialty lied in depicting these scenes on fabric through looms with minute details such as royal noble dresses, carpets, chairs and throne. People often confused these designs with paintings on a canvas.

After the flooding of a tributary of Ganga (Bhagirathi), the Baluchar village got submerged in water and the artisans had to resort to safer locations, leaving behind the facilities and infrastructure provided to them by the Nawab. The weavers relocated to Bishnupur, which came under Bankura kingdom under the reign of Malla dynasty. Due to relocation, absence of patrons and immense pressure from British government to make weavers switch to other professions, the craft saw a decline and very few ardent weavers could continue. Dubraj Das was the last known weaver of the Baluchar village, who died in 1903. He used to sign his saris like an artist’s artworks, a rare phenomenon by any artisan. The saris signed by him are still being found and procured.

In 1956, Subho Thakur, a famous artist himself took to revive this weaving tradition. He invited a master weaver named Akshay Das to the Regional design center, where he himself was serving as the Director and trained him in the technique of Jacquard weaving. They both studied the Baluchari saris procured from the family collection of Rabindranath Tagore. Akshay then worked tirelessly to hone his skills and train the other artisans of Bishnupur. Hence, the town re-emerged as a weaving center for the famous Baluchari silk saris.

The saris woven in Baluchari tradition are characterized by elaborate motifs on border and ‘Pallu’. Traditionally, scenes from religious epics and courtly ceremonies constituted the motifs in Baluchari weaves. The artisans also started accommodating Persian miniatures and images of sculpture and paintings from temples or monuments in the weaves. In 1957, Sri Das introduced Ajanta Eldora cave paintings as motifs on Baluchari saris. The weaving duration of one such sari is around 15-18 weeks; the process involves expensive raw material and labor intensive technique.

The artisans of Bishnupur now source mulberry silk from Bangalore and Mysore, which is first boiled in soda and soap mixture and then dyed in acidic colors. The yarn is then transferred to small beams called ‘Sisaban’ and bigger beams called ‘Dhal’. While weaving, the artisan attaches these beams on the loom and starts weaving.

The native weavers of Baluchar used Jala looms; a Jala is a design reference through which many designs can be made. A Jala lasts for almost 100 years. The artisan first finalizes his design on paper, it is then passed on to fabric using Machan and threads, which becomes the master sample. A copy of master is also made on loom and kept safe by artisan, just in case if jala gets spoiled he can make a new copy from it. The saris produced were reversible, the motifs could be seen and understood on either sides.

With the arrival of Jaquard looms, jala system is now replaced by punched cards. The designs are now drawn on graph paper and then the jacquard artisan starts punching cards as per the design; the punched cards are afterwards seamed in sequence and fixed in the Jacquard machine. The use of Jacquard has reduced the weaving duration of Baluchari sari to six days, when 2 artisans work in shifts, but the sari motifs are no longer reversible. Though the ancient village of Baluchar is now submerged under the natural weave of Bhagirathi and its tributaries and distributaries, the tradition of weaving on the looms is being carried forward by the young generation of weavers in the town of Bishnupur. The old took away a dimension of stories with it but another one is being pulled back and embellished with new images and depictions. Text & images by ~ Parul Bajoria ( Miharu Designs)

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Artisans at 'Miharu' |

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | ♦ The items in this category are non refundable but you may exchange this product with any other product from the same category. ♦ The products in this category is handmade. ♦ The product is only eligible for a refund in the case of damage or defect. |

| Material | |

| Made of | Silk |

| Instruction | |

| Note | The product is hand woven; gentle hand-wash or dry clean is recommended. These might slightly differ from as seen on digital screen. |

| Restrictions | |

| COD - Option | Not Available |

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

/26_01_2021/Winter-s-Call-❁-Bandhani-Shawl-❁-22-225x150h.jpg)

/25_01_2021/22-(2)-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)