- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Knots & Dots by Khatri Talha

- Product Code: 2035-NC22-30

- Weight: 500.00g

- Dimensions: 30.00cm x 25.00cm x 10.00cm

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

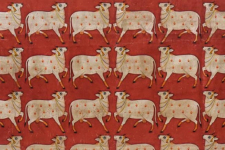

A familiar chatter swells in the air as feet chase the trail of a carelessly flying odhani in the by-lanes of Bhuj, spilling colors all over. While the women are busy tying knots in fabric, their whispered secrets quietly sneak into these tied bundles. They remain unnoticed but intact till the connoisseur hands unfurl the knots and set the stories free to engulf the wearer. Bandhani is not merely a fabric; it’s a canvas of anonymous tales soaked in many colors and ensuring that the wearer is wrapped in the warmth of native emotions.

Bandhani is an expression used in Gujrat for textiles where different designs are produced by tying individual parts of the fabric before dyeing. The Gujrati word‘Bandhavun’ is derived from the Sanskrit word for tying ‘Bandhan’. The people engaged in producing designs on fabric as a result of tie-dying technique are known as ‘Bandhej’.

The tie and dye art of treating textiles is fairly universal, with many ingenious versions scripting new genres in various parts of the world. The technique of resist dying by binding the individual parts of the cloth to shield them from the dye is usually known in India as ‘Bandhani’. There is ample evidence to suggest that the relatively complex process of mordant-dyeing was known to the inhabitants of the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro in about 2000 BC. So, it is possible that resist dyeing was also practiced. Archival facts further confirm that in 6th-7th century A.D Bandhani cloth was depicted on walls of the Ajanta caves. Here women are shown wearing bodices in a simple dotted tie and dye pattern, as well as skirts apparently made in Ikat fabric (another resist dyeing technique still wide spread in India). More recent to these paintings are the written references to Bandhani, which appears in the much quoted Harshacharitra by Bana (the court poet of king Harsha of Kannauj), where he celebrates the dyed patterns on the bride’s special odhani, an auspicious garment which is traditionally tie and dyed even today.

Adored by almost all women alike, Bandhani is highly popular amongst theKumhar, Jat, Harijan, Meman and Rabari communities. The art of tie and dye assumes a different expression in every house. For instance, while the Rabaris prefer black stole with red dots dyed on wool, the Muslim population around here has great cultural sentiment attached to a large known as chandrokhani which is wrapped around for occasions like marriage. The Khatri, Parsi, Meman and Sonaar communities have a particular penchant for Bandhani on silk.

The main clusters practicing this craft have settled in Mundra, Mandvi and Bhujareas of Kutchh. Bhuj is infact the main center for the traders of dyes and colors used in this craft. The fabric required for this art is sourced from Bangalore, Mumbai, Bhagalpur, Ahmadabad and Surat.

The fabric to be dyed is first carefully examined for quality by the cloth dealer. Then the layout pattern is marked after folding the fabric into four or more layers. Fields are delineated using a cord dipped in Geru (burnt sienna mixed in water). Consequently wooden blocks of desired motifs are dipped in the same Geru mixture and stamped within the marked fields.

The task of tying of motifs is predominantly carried out by the womenfolk who manage this along with the rest of the household chores at their homes in the village. The thread used for tying is usually plain cotton yarn which is mostly collected from industrial waste. It is led by the thumb and the forefinger of the right hand and is made to run through a fine millet stem bobbin, so that it runs smoothly and evenly. Knots are tied in two ways. One option requires raising the folds of the material with the pointed nails of the finger to create a little bunch around which thread may be tied. The second option requires use of filler materials, which are impregnated within the knots. A single stole can have 4000 to 5000 knots. More interestingly, women can tie up to 700 knots in a single day. It’s relatively easier tying knots in silk or cotton for the woolen knots have to be reaffirmed by biting them with the teeth.

by immersing the tied fabric in a hot solution of dyes. It is finally rinsed, squeezed and dried. There is limited use of natural dyes in this process.</p>

<p><a href=)

The textile can even be touched upon by manual application of certain colors for selective dying. Fast dyes, which can be directly applied, have made this process simpler. This technique is known as lipai. Naphthol dyes are effective in cold solutions and can be used to dye the next darker color. The dyed textile is washed by local washer men and starched if necessary.

The ties of the folded Bandhani textile remain closed till they are sold or at the most opened at one corner to show the color scheme. For opening, the Bandhani material is pulled crosswise forcibly so that all the ties open up simultaneously as all the threads are rendered loose.

In his pursuit to learn more about the craft Jabbar bhai ventured into the world of tie and dye in 1992. He grew up watching his mother, sister and other ladies at home dedicatedly tying knots into the fabric. His curiosities lead him to learn further about dyeing and coloring from his relatives and friends. The first one in his family to set up a tie-dye unit, he has earned the status of a master with his persistence and good sense of design. Today, Jabbarn Bhai works with the leading designers of the fashion industry.

There are about a 100 such workshops in Bhuj today and a good 1000 people are still engaged in this craft here. Interestingly the designs have peculiar names such as shikaari, kabootarkhana etc.

Bandhani is as popular today as it has always been. These tie and dye motifs for one, will never go out of fashion for the simple reason that womenfolk all over the country identify themselves with it. From draping the newly wed bride to becoming a constant companion as a chunri or odhani, these myriad Bandhini patterns run skin deep till they get absorbed by the soul.

~

For more on Bandhani visit - Research & Archive section

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Talha Khatri |

| City | Bhuj |

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | ♦ The items in this category are non refundable. ♦ The products in this category is handmade. ♦ The product is only eligible for a refund in the case of damage or defect. |

| Material | |

| Made of | Tussar Silk |

| Instruction | |

| About Sizes | 236 x119 cms. |

| Note | As each piece is hand printed and unique, expect some variation from shown design. |

| Care | We advise dry cleaning it for the first time and subsequently hand wash with a mild detergent like Eazy or Genteel. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-234x234h.jpg)