Gujarat's diversity is mirrored in a rich assortment of handicrafts, from embroidery, beadwork, wood crafts weaves, and pottery to tribal arts. A beautiful amalgamation of artwork exists here as each district specialises in a different art form.

1. PATOLA

Ikat is a fabric with diverse histories owing to its multiple origins; however, the name is a Malay word literally for ‘to tie’. It is a weaving technique where in the weft, the warp or both the yarns are dyed selectively through a resist-dye process so that the patterns emerge upon the criss cross of the yarns. Patan, the former capital of Gujarat is the home for double Ikat, which incorporates a very high level of intricacy and skill. It starts with dyeing both the warp and the weft and matching them to form motifs at regular intervals. This requires pre calculation of where the dye should come on the yarn (warp or weft), for it to accurately form an overlap with the same or different colored stretch on the second yarn (weft or warp), to weave a majestic double Ikat fabric called Patola.On a Patola, the square represents security in every aspect of life. The elephant, parrot, peacock and kalash (metal pot) are considered saubhagya & (good luck). To cater to more lovers of Patola, a simpler version with similar visual effect but lesser intricacy and therefore lower price range was invented. The Single Ikat Patola of Surendranagar and neighboring villages came to the rescue of the weavers, the technique and the buyers in the region.

2. AJRAKH

A king once grew so fond of his bedspread that he insisted his maids to let it stay on his bed for one more day, he muttered “aj ke din rakh”, the phrase which went on to be used to name that uniquely printed fabric as Ajrakh. It is also believed that the fabric derived its name from the sanskrit word ‘A-jharat’ or ‘that which does not fade’. ‘Azrak’, the Arabic word for blue could have also played a role in its etymology because of extensive use of indigo in the process. Ajrakh originated in the provinces of present-day Sindh in Pakistan and the neighboring districts of Kutch in Gujarat and Barmer in Rajasthan. Although Ajarakh printing is a part of Sindh, during the Indus Valley Civilisation, its roots extended to the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat in India. The Indus River proved to be an essential resource for washing fabric and acquiring raw materials like indigo and cotton which were ample along the river. The ingredients are all obtained from nature- from herbs, vegetables, and natural minerals. Camel dung is used as an ingredient to remove stretch from the fabric. The natural dyes used in Ajrakh printing expand the pores of the fabric during summers, making it easier for air to pass through. During winters the pores of the fabric close, proving warmth.

3. ROGAN ART

Rogan Art, an ancient skill with its origins in Persia, came down to Kutch around 400 years ago. Traditionally, the craft was pursued to beautify bridal clothing of the regional tribes, beautiful borders and floral patterns on Ghagras, odhni and bead spreads were painstakingly painted.For bearers of the seven generation old art are the Khatri family, for they appear to be the only family practicing the little known art in the small village called Nirona in Kutch. The process is time consuming. First the rogan (which takes its name from the Persian word ‘oil-based’) has to be prepared by heating castor oil to boiling point over three days, cooling it and then as it thickens, mixing in appropriate amounts of colors. The pastes of yellow, red, white, green, black and orange are kept in earthen pots with water to keep them moist. A thin iron rod, flat at both ends, is used to paint. The painting takes quite some time to be done on a small piece of cloth, depending upon the intricacy of the work and the type of cloth. If the work is very intricate, then a square foot piece of cloth could take around a month. The work takes time because first the outlining is done, then the work is filled, then after drying, the colors are added and then the work is done again. Drying generally takes two days. In case of symmetric patterns, to reduce the effort, the fabric is folded from the centre to get the impression on the other half, this also helps in creating effects like the background and the foreground.

4. BANDHANI

Bandhani is an expression used in Gujrat for textiles where different designs are produced by tying individual parts of the fabric before dyeing. The Gujrati word ‘Bandhavun’ is derived from the Sanskrit word for tying ‘Bandhan’. The people engaged in producing designs on fabric as a result of tie-dying technique are known as ‘Bandhej’. The tie and dye art of treating textiles is fairly universal, with many ingenious versions scripting new genres in various parts of the world. The technique of resist dying by binding the individual parts of the cloth to shield them from the dye is usually known in India as ‘Bandhani’. There is ample evidence to suggest that the relatively complex process of mordant-dyeing was known to the inhabitants of the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro in about 2000 BC. So, it is possible that resist dyeing was also practiced. Bandhani is highly popular amongst the Kumhar, Jat, Harijan, Meman and Rabari communities. The art of tie and dye assumes a different expression in every house. For instance, while the Rabaris prefer black stole with red dots dyed on wool, the Muslim population around here has great cultural sentiment attached to a large known as chandrokhani which is wrapped around for occasions like marriage. The Khatri, Parsi, Meman and Sonaar communitie have a particular penchant for Bandhani on silk.

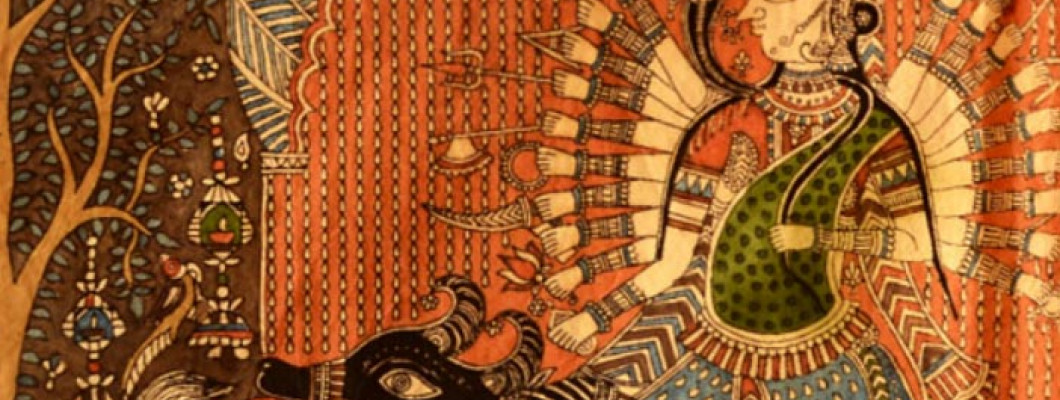

5. MATA NE Pachedi

In a great battle between Shiva and the asura (demon), Raktabija, every drop of the asura’s blood that fell to the earth, gave rise to more and more demons. The gods then turned to Shakti, the goddess Durga, to annihilate the asuras. The fierce goddess pierced the demon’s body and drank all his blood, thus saving both the worlds. The goddess in her seven forms is now worshipped during the nine days of Navaratri festival. Mata ni pachedi literally means “behind the mother goddess”, and is a cloth that constitutes a temple of the goddess. When people of the nomadic Vaghari community of Gujarat were barred from entering temples, they made their own shrines with depictions of the Mother Goddess on cloth. This ingenuous solution is believed to be the origin of Mata ni Pachedi, the sacred art, which is now revered by all. The painting usually has a set pattern, with the mother Goddess dominating the central area in her mighty form, surrounded by deities and commoners worshipping her with equal reverence.

Mata ni Pachedi is also known as the “Kalamkari of Gujarat”, owing to its similarity of the Kalamkari practiced in Southern India and the use of pens (kalam) fashioned out of bamboo sticks, for painting. To quicken the process and meet demands of villagers, who would commission paintings to offer to the mother goddess on fulfillment of wishes, the painters started using mud blocks for printing. These blocks were large and coarse, and after using a few times, would be thrown in the river where they returned to the soil. Over the course of time, wooden blocks replaced mud blocks, facilitating the use of finer motifs. Yet, the craftsmen still often make the entire painting with the bamboo “kalam”, using blocks only for printing the borders.

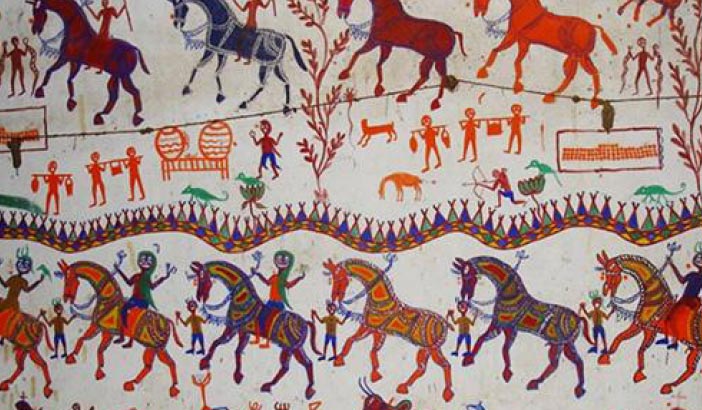

6. PITHORA

The Pithora paintings trail back long into history and find their roots in the cave paintings, thousands of years old. This is the most prevalent and characteristic art tradition of the Rathwa community, who live in the region bordering Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh states in India. While the styles vary with every Bhil group, they hold a deep social relevance. Pithora paintings are characterized by the seven horses representing the seven hills that surround the area where the Rathwas reside. This is enclosed within a rectangular fence in the painting that defines thisgeographical area. This rectangle usually extends up to the Arabian Sea in the west, Bharuch in south and Indore in north and east. The wavy line depicting the river Narmada cuts through the painting.Things like fields, trees, farms, wild life, birds, sun and moon are present in their relative positions in the map along with people and their ancestors. Even modern elements like railway tracks, aeroplanes, and computers feature in the paintings, thus making the Pithora paintings a real description of the world of Rathwa tribe. Pithora painting has various connotations. One meaning attached to the Pithora Paintings is the idea of a map. This tradition is supposed to have started in the 11th century, when Bharuch was a centre for traders from the North. Pithora paintings are sometimes considered very sacred. The Rathwas consult the village Tantrik (witch doctor) to heal illnesses and undo bad omens. If a wish made to “Baba Pithora” is granted, a Pithora painting has to be made in the main wall of the house, in consultation with the Tantrik.

7. MASHRU

It is not just kaleidoscopic embroideries that Gujarat is so famous for; it is also the home of wonderful weaves that combine impressive skill and generations of expertise, with the result of pure aesthetic joy. Reaffirming that appearances are deceptive, the spectacular Mashru weaving has the appearance of glistening silk that conceals the soothing feel of cotton. Mashru has characteristic bright contrasting stripes in vibrant colours, instantly uplifting the spirits of a desert traveler. It seems that to make up for the lack of colour in the dry barren deserts, the makers of this fabric put every possible colour together in wonderful, lustrous compositions. Blending the opulence of silk and the comfort of cotton, this magic fabric in its multicoloured stripes and ikat patterns has been a favourite among those with a taste for luxury. Mashru is not just a luxurious fabric; it also has a very practical utility. While the silk on the outer surface has a beautiful, glossy appearance, the cotton yarns in the back soak up sweat and keep the wearer cool in the hot climate of the deserts. Mashru weaving is an old tradition in India and this textile was traded to Arabian countries. Mashru means “permitted” in Arabic and it is believed that this textile got this name when Muslim men, who were not allowed to wear silk, started wearing this fabric. Since the body is in contact with cotton and silk is only the exterior, they got approval to wear this luxurious fabric. Slowly, it became liked by Hindus also and these days, this fabric can be seen in the clothes of Kutchi nomads. While the small dotted pattern is preferred in Anjar, Kutch, thestriped ones are liked all over the country. Traditionally used in garments, Mashru is also used for making quilts, cushions and bags. The craftsmen have also developed ne designs, by tie-dyeing the fabric using ‘Bandhani’ technique.

8. KUTCH Embroidery

Gujarat is famous all over the world for its embroideries and mirrorwork. There are about 16 different types of embroideries done in the Kutch region, but the most well known one, with its chain stitches and countless mirrors, is the Rabari embroidery.It gets its name from the Rabari community, who are a nomadic / semi-nomadic community of cattle raisers living in the western region of India, from Rajasthan to the Kutch region in Gujarat. They migrated into this region from Sindh (now in Pakistan) about 400 years ago and many of their relatives still live there. They have wonderful stories about their origin, ranging from a connection with Shiva to Rajputs going outside their territories. Rabari, or “Rahabari” means one who lives outside or “goes out of the path”. As the type of embroidery on the garment clearly distinguishes the person’s identity, the different communities of Rabaris can be identified from the type and placement of embroidery on their odhanis (veils for head and shoulders). For examples, the Wagadia Rabaris wear odhanis with embroidered borders while the Kachela Rabaris have designs in the centre of the odhanis. Rabari embroidery is characterized by chain stitches and a generous use of mirrors. The women depict the world around them, without the help of sketches or patterns. The only material used is a simple needle and thread, which they purchase from Bhuj, the nearby town. The stark landscape of Kutchh with its thorny babool and keekar bushes is given a new dimension with colours, by the vivid imagination of Rabari women, through chainstitches decorating the surface of cloth.

9. GAMTHI PRINT

Gamati print originated from the humble villages of Gujarat and Rajasthan. Gamthi print uses vibrant and bold colors and varied, intricate patterns. Elements used in this technique are mainly inspired by nature. Originally, natural dyes were used, but today they have been replaced by chemical and artificial colors. The main colors used were, green from henna, yellow from turmeric, blue from indigo, and black from rusting iron, about 27 different colors could be achieved through plant parts and metals. Made of seasoned teak wood, blocks are the main tools of the printer. With designs etched on the underside and two to three cylindrical holes drilled vertically and horizontally across the body of the block, the block makers of Pethapur ensure free air passage and release of excess printing paste, making their blocks so special.

10. LAQUER WORK

Passing by the tiny lanes of narrow Kutchhi houses of Nirona, you will find clusters of various art forms. The local Vadha community, a nomadic tribe in Kutch practise lacquer wooden art. Using simple hand-held machines, and locally sourced baboon trees, toys, spatulas, rolling pins and other kitchen accessories are crafted. Lac resin was obtained from some special insects found in the village. It is then mixed with natural colours from the bark of trees and stones to create different colours and textures. These textured designs are then coated with natural groundnut or coconut oil to give them a sheen. It also helps the colours last longer.

Leave a Comment