Bihar is a treasure trove of traditional art and crafts, each with its own unique charm and history. Madhubani painting, known for its intricate patterns and bright colors, brings mythological tales to life. Sikki grass craft turns simple golden grass into beautiful baskets, dolls, and home decor. Sujani embroidery, once used to upcycle old fabrics, now features delicate hand-stitched motifs narrating everyday life. Bhagalpur is famous for its silk weaving, producing some of the finest tussar silk in India. From paper mache to Manjusha art, the famous crafts of Bihar are a testament to the creativity and skill of its artisans. explore 10 Famous Handicrafts of Bihar.

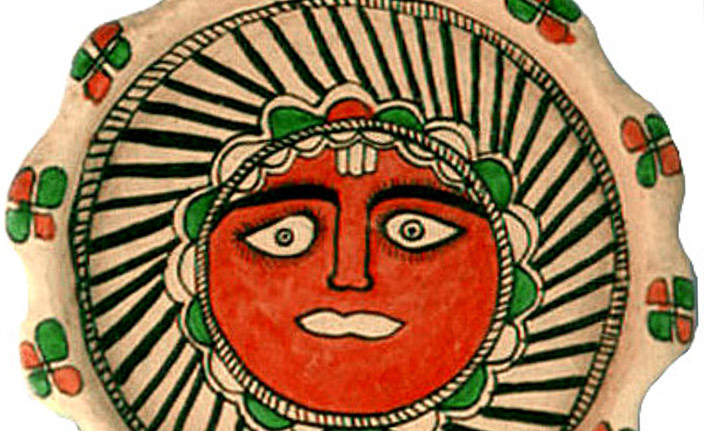

1. Madhubani Painting

Madhubani painting, literally meaning the "Forest of Honey," is one of the oldest and most celebrated folk art forms of India, originating from the Mithila region of Bihar. With a history deeply intertwined with mythology, it is believed that this art form was first created during the wedding of Sita and Rama, as mentioned in Tulsidas’ Ramcharitmanas.

Traditionally, Madhubani paintings were created as wall murals (Kohabar) and floor paintings (Aripana) in homes, depicting themes of love, fertility, devotion, and nature. They were drawn with natural colors sourced from plants, metals, and household ingredients, charcoal for black, turmeric for yellow, flowers for red, and leaves for green mixed with resin and gum for durability. The artists used fine bamboo twig brushes for detailing and cloth-wrapped twigs for filling spaces.

Distinct styles emerged based on social structure—Brahmin artists favoured bright hues, while the Kayasthas preferred muted tones. The Harijan style involved a base wash of cow dung for an earthy finish. Over time, with changing mediums, these paintings transitioned onto handmade paper, canvas, and fabric, making them more accessible and marketable.

Madhubani paintings often depict Hindu deities, local flora and fauna, celestial bodies, and geometric patterns. Originally a ritualistic expression confined within households, Madhubani paintings have now found global recognition, adorning greeting cards, textiles, and home décor.

Buy Madhubani Painting

2. Sujani Embroidery

In the quiet village of Bhusara, Bihar, women once gathered around old, worn-out sarees, their needles weaving stories of faith, life, and struggle. This was the birth of Sujani embroidery, an art form deeply rooted in tradition and storytelling. Stitched with crimson and yellow threads, red for blood and life, yellow for the sun, a piece was more than just fabric; it was a prayer, an offering to Chitiriya Maa, the ‘Lady of the Tatters’. The motifs spoke of ancient beliefs, serpents coiling beside fish, elephants marching through forests, and Rama’s grand wedding procession. Every stitch carried whispers of devotion, of generations of women passing down their silent narratives, their joys, and their sorrows.

But as time turned its pages, Sujani took on new voices, no longer confined to myths and rituals. It became a canvas of resistance, a needle-woven testament to the realities of rural life. Scenes of girl children seeking education, women defying oppression, and echoes of societal change emerged in its patterns. What was once a sacred ritual, is now a thriving craft, adorning sarees, wall hangings, and garments, carrying the legacy of its makers to the world. With a Geographical Indication (GI) tag and the 2019 UNESCO Seal of Excellence, Sujani stands today as a living testament to the resilience and artistry of Bihar’s women, their stitches binding past and present in a tapestry of tradition and transformation.

3. Bhagalpur Weaving

Bhagalpur, a major tussar silk weaving hub in Bihar, is known for its high-quality silk fabric, traditionally dyed in bright colors like red, blue, pink, and orange. The fabric is woven from the Antheraea mylitta silkworm, which feeds on local forest trees. Characterized by its textured surface with patterned stripes and checks, Bhagalpuri tussar silk is crafted by thousands of skilled artisans using traditional four-shaft pit looms, locally called khatkal.

Bhagalpuri tussar silk has been in demand for centuries, both in India and abroad. During British rule, it was exported to Europe at high prices. However, with the rise of synthetic fabrics and mill-made silk, its production declined. Efforts to revive this craft began in 1993 with financial support from organizations like Dastkar and BMKS, leading to employment programs and technical innovations. In 2013, Bhagalpuri silk received Geographical Indication (GI) status, recognizing its unique heritage and craftsmanship. Today, Bhagalpur remains a key center for tussar silk production, with artisans continuing to innovate while preserving this centuries-old weaving tradition.

4. Khatwa applique

Khatwa, the traditional applique craft of Bihar, involves layering fabric to create intricate ornamental or narrative textile designs. Historically, this technique was used to craft elaborate tents (kanats) and canopies (shamianas) for royalty, featuring bold, geometric, and figurative motifs. The craft shares visual and thematic similarities with Madhubani and Mithila paintings, incorporating domestic imagery such as stoves (chulha), knives (hasiya), and household utensils, along with depictions of men and women in nuptial settings. Traditionally, artisans used a vibrant red or orange base fabric with white applique work. However, with the decline of royal patronage during the colonial period, the craft saw a downturn until its revival in the 1970s.

During this revival, supported by organizations like the Ford Foundation and national NGOs, khatwa transformed in both colour palette and application. The base fabric shifted to light shades of white or off-white markeen, with brightly coloured applique work, reversing the earlier colour scheme. Silk thread embroidery, including running and chain stitch techniques, became an integral part of the designs. No longer limited to tents and canopies, khatwa began appearing on garments, saris, stoles, wall hangings, cushion covers, and bags, ensuring its continued relevance in contemporary textile traditions.

5. Sikki Grass

Sikki grass is a traditional craft that dates back to the Vedic era and is primarily produced in Bihar's northern region and a few locations in Uttar Pradesh. Sikki grass is a traditional craft that dates back to the Vedic era and is primarily produced in Bihar's northern region and a few locations in Uttar Pradesh. Sikki grass is a traditional craft that dates back to the Vedic era and is primarily produced in Bihar's northern region and a few locations in Uttar Pradesh. Sikki craft, an ancient art form dating back to the Vedic period, is an integral part of Bihar’s cultural heritage. Primarily practiced in the northern regions, particularly in the Madhubani district, this craft revolves around the use of sikki grass, a golden-hued natural fiber that flourishes during the monsoon season. Once harvested, the grass undergoes a drying process under the sun for 20-25 days, acquiring its characteristic luster. Traditionally, Sikki craft began as a pastime for women, who wove baskets and storage containers for food, jewellery, and household essentials. Over time, their creativity evolved, leading to the commercialization of the craft. The process involves two main types of grass—khar and sikki—where khar, a sturdier variety, forms the base, and sikki grass is wrapped around it to create intricate patterns and structures.

The artisans use simple yet effective tools like iron needles, knives, and scissors to shape and weave the grass into elaborate designs. Sikki products are deeply embedded in local life, with items such as dalia (storage baskets), munari (small containers), daura (offering baskets), and chatai (mats) being widely used. Beyond household items, the craft has extended to home décor, with roofs, decorative pieces, and even artistic figurines made from sikki grass.

6. Tikuli Art

Tikuli art, deeply rooted in Bihar’s cultural heritage, derives its name from the local term for "bindi," the ornamental dot traditionally worn by women between their brows. Originally, the bindi symbolized intellect and modesty, but over time, Tikuli art has transformed into a medium of empowerment for women, particularly in the Danapur region of Patna. Historically, Tikuli was crafted using molten glass, which was intricately painted with natural colours and adorned with gold foil, making it a luxurious accessory reserved for royalty. The level of detail and embellishment determined its value, and it flourished under Mughal patronage. Traders from northern and western India travelled to Patna to procure these finely crafted Tikulis. However, the craft faced a sharp decline after colonization, and by 1900, it was nearly extinct.

A revival of Tikuli art began in 1954 when Padmashree Upendra Maharathi, inspired by Japanese hardboard paintings, introduced a new method of depicting Tikuli motifs on glazed hardboard. This innovation helped preserve the craft and gave it a fresh commercial appeal. Since 1974, painter and craftsman Ashok K. Biswas, alongside his wife, entrepreneur Shibani Biswas, has played a crucial role in reviving and popularizing Tikuli art. The process involves preparing a wooden base, repeatedly smoothing it with sandpaper to achieve a glossy, dark surface resembling polished granite. Artists then use enamel paints and fine brushes made of sable or squirrel hair to create intricate designs in harmonious primary colour schemes. Over time, the themes, compositions, and colour palettes have evolved, and the durability of enamel paint has allowed artisans to expand Tikuli art into practical items like coasters, trays, and mobile stands, ensuring its continued relevance and sustainability.

7. Paper mache

Paper Mache, derived from the French term meaning “chewed paper,” is a traditional craft that involves molding paper pulp with an adhesive to create a variety of artistic and functional objects. In Bihar, the craft flourishes in Salempur, a village in the Madhubani district, where women, alongside their agricultural work, have been practicing this unique art form. Paper Mache objects from Bihar include traditional and symbolic forms such as diyas (lamps), haathi (elephants), and kohbar (sacred nuptial chamber motifs). The Kohbar, a hut-shaped structure, holds deep cultural significance in Bihari weddings. According to local tradition, after marriage rituals, the groom places sindur (vermilion) on the Kohbar for an auspicious beginning as a newlywed couple.

The process of making paper Mache involves mixing paper pulp with adhesive, shaping it into desired forms, and then coating it with a layer of Multani Mitti (Fuller’s earth). Once dried, artisans smoothen the surface using sandpaper, preparing it for intricate hand-painted designs, often inspired by Mithila art.

The craft in Salempur gained prominence largely due to Subhadra Devi, a highly skilled artisan who was recognized and encouraged by the Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) to refine her expertise. She blended traditional motifs with this relatively modern technique, adorning her paper mache creations with Mithila painting, an iconic folk art of Bihar. Her contributions earned her the State Award (Bihar) in 1980 and the National Award in 1992. She also played a key role in training a new generation of women artisans in Salempur through a training program initiated 20 years ago.

8. Stone Art

Bihar’s stone craft is an enduring testament to the skill and perseverance of its artisans, who have been shaping history—quite literally—through their chisels and hammers. One of the most prominent centers of this craft is Pattharkatti, a village in the Gaya district, where generations of artisans have dedicated themselves to transforming rough black granite into exquisite sculptures. The name Pattharkatti, meaning “cut-stone,” is a tradition that dates back centuries. The origins of this craft in Bihar can be traced to the 18th century when Rajasthani stone carvers settled here, passing down their expertise to the local population. Over time, this knowledge evolved into a highly specialized art form, with artisans perfecting their ability to bring life to stone.

A single miscalculation in measurement can compromise the aesthetics of the final piece. Using traditional tools along with modern scientific instruments, artisans assess the depth, texture, and hollowness of the stone before chiseling intricate details. The finished sculptures range from deities and historical figures to abstract and contemporary forms, each carrying a silent yet profound narrative.However, the increasing popularity of mass-produced sculptures has disrupted their market, making it difficult to sustain their craft. Yet, their passion remains unshaken. As one artisan, Ravindra Nath Gaud, eloquently puts it, “Statues are life for us.”

Recognizing the significance of this craft, the government of Bihar and various NGOs have stepped in to support the artisans through initiatives like the Vishwakarma Vikas Yojana and the Pattharkatti Craft Village. These programs provide training, resources, and opportunities to ensure that the legacy of Bihar’s stone craft not only survives but thrives in the modern era.

9. Bawan Buti

The Bawan Buti sarees, named after the fifty-two motifs intricately woven into their fabric, are a lesser-known yet historically rich textile tradition from Bihar’s Nalanda region. This area, known for its deep Buddhist roots since the fifth century, has influenced the craft's motifs, which often depict Buddhist iconography such as the Bodhi tree, wheel of religion, golden fish, and conch. Traditionally, weavers designed patterns inspired by their surroundings, incorporating elements like flora, fauna, and socio-economic symbols of their time. Woven painstakingly using frame and pit looms, the sarees employ the extra-weft technique, a labor-intensive method that adds decorative motifs to the fabric. The country’s first president, Rajendra Prasad, even commissioned curtains featuring these fifty-two butis for the Rashtrapati Bhawan, highlighting the cultural significance of this weave.

During the late 18th century, the craft saw an evolution with the intervention of Upendra Maharathi, an Odisha-based artist and Rabindranath Tagore devotee. He introduced approximately 200 new motifs, including the lotus flower, ducks, tree of life, and human figures, though many of these designs have since been lost to time. Despite changing aesthetic demands, Bawan Buti sarees have retained their distinct symmetrical patterns and complex craftsmanship. Today, two key centers continue to produce these exquisite weaves: Nepura, known for its fine Tussar silk variations, and Baswan Bigha, where cotton Bawan Buti sarees are still handcrafted, preserving the legacy of this centuries-old tradition.

10. Manjusha Art

Manjusha, a beautifully decorated basket used in the Manasha Puja, is an integral part of the cultural heritage of Champanagar, Bhagalpur. This sacred tradition, observed primarily in August, involves reciting the Vishahari Gatha, a poetic narrative of the tragic tale of Behula and Lakhindar. Originally, 20-30 families in the region crafted these intricate baskets, using locally sourced minerals to create line drawings on their surfaces. Over time, these artistic depictions evolved into the recognized Folk Art of Manjusha painting, characterized by its bold, linear forms and vibrant storytelling elements. The Manjusha itself is a square structure made from paper or thermocol sheets and bamboo sticks, crowned with a pyramid-like top reminiscent of a char-bangla house. The walls of the Manjusha are adorned with illustrations portraying Behula’s trials, often showing her holding snakes, supporting her deceased husband Lakhindar, or encountering mythical figures like Tunhi and Natula.

Rooted in the historical and mythological past of Champa, the ancient capital of Anga, the art and symbolism of the Manjusha reflect the region’s deep cultural lineage. Champa, mentioned in the Mahabharata and various Puranas, was a significant trade hub connected to Magadha, the Maurya, Gupta, and Pala dynasties. The Manjusha paintings, inspired by the Vishahari Gatha, prominently feature Behula and various forms of snakes—floating on water, three-headed serpents beside her, and a five-headed snake near Lakhindar’s body. Other motifs such as the sun, moon, trees, elephants, and fish are also present, each carrying symbolic meaning within the narrative. While traditional Manjusha paintings employed simple, naturally sourced colours, modern adaptations incorporate commercial art influences.

Leave a Comment