Uttar Pradesh is renowned for its rich Ganga-Jamuni culture, where the Ganga and Yamuna rivers bind the state together. As history shows, civilizations have flourished along rivers, and Uttar Pradesh is home to some of India’s oldest legacies. Many great Indian personalities have deep connections with this land. The diversity of crafts in Uttar Pradesh is vast, shaped by the contributions of various cultures over time. Across its ancient towns and bustling cities, artisans shape stories in silk, marble, wood, and clay, carrying forward traditions that have withstood the test of time. From the shimmering brocades of Banaras to the delicate embroidery of Lucknow, from the fragrant attars of Kannauj to the intricate inlay work of Agra, each craft is a testament to centuries of cultural confluence and artistic mastery. While it is difficult to encompass them all, we have categorized them based on scale and identity. Here is a list of 10 famous arts and crafts of Uttar Pradesh.

1. Brocade of Banaras

Banaras, also known as Kashi, has one of the world's oldest weaving traditions, dating back to the Vedic period. Banarasi brocade is a rich fabric made from silk or cotton, woven with gold or silver threads. These sarees are known for their intricate floral and foliate patterns, paisley (kalka), and vine-like designs (bel), with a row of upright leaves (jhallar) along the border. Other key features include detailed pallus, net-like patterns (jal), fine mina work, compact weaving, and a shimmering metallic effect. Depending on the complexity of the design, a single saree can take between 15 days to six months to complete. The weavers of Banaras, known as Tantuvayas, have been crafting these textiles since 1500–500 BC, as mentioned in ancient Vedic texts. Banarasi fabrics come in four main types: Georgette (lightweight), Shattir (a silk-cotton blend), Kora Organza (silk with zari), and Katan (pure silk). Banarasi Jamdani, a special variation, features floral and geometric patterns woven into the borders, pallu, and body. Common designs include Laharia (wave-like patterns), Harava (vertical lines with floral motifs), Kharibel and Patri (horizontally running figures), Jaldar (net-like patterns), Phuldar (floral shapes), Buta (single motifs), Fardibuti (tiny dots), and Masurbuti (small lentil-sized motifs). This age-old craftsmanship, passed down through generations, continues to make Banarasi brocade a symbol of elegance and tradition.

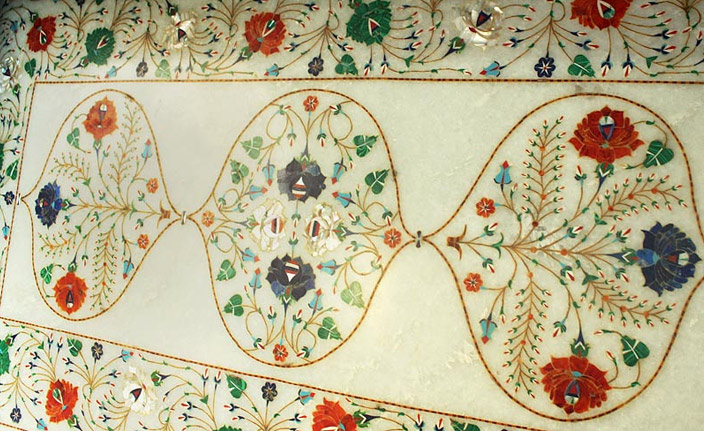

2. Pacchikari of Agra

Pacchikari, the Indian adaptation of the Florentine craft of Pietra Dura, was introduced to India by skilled artisans brought in by the Mughal Emperor from Persia. This intricate inlay work, predominantly practiced by Muslim artisans tracing their lineage to those who worked on the Taj Mahal, remains a hallmark of Agra’s craftsmanship. The craft primarily uses Makrana marble, the same fine-quality stone used in Mughal architecture. The process involves multiple specialists, beginning with the shaping of marble, followed by the creation of intricate designs. The surface is coated with geru, a red mineral color that highlights the etched patterns. Using only chisels and a set-square, without hammers, artisans carefully carve shallow grooves into the marble. Semi-precious stones like malachite, cornelian, jasper, pearl, and coral are then ground and shaped using a hand-operated emery wheel. The carved grooves are filled with cement, and after a slight heating of the marble, the stones are delicately inlaid. This meticulous technique, preserved through generations, continues to define the exquisite artistry of Agra’s pacchikari, seen in monuments and decorative objects that echo the grandeur of Mughal craftsmanship.

3. Wooden toys of Banaras

As settlements flourished along the banks of the Ganges, Varanasi became a hub of art, craft, and music, fostering a rich cultural heritage. Among its many traditional crafts, wooden toy-making stands out as a skill passed down through generations. Originally, the craftsmen of Varanasi specialized in ivory carving, but with the government ban on ivory, they transitioned to wood carving. Today, the craft is practiced in colonies like Kashmiriganj, Khojwan, and Bhelupur, where over 200 families are involved in different stages of toy-making.

The craft is divided among artisans with specialized skills—some focus on carving and shaping the wooden toys, while others are responsible for painting them. Selecting the right wood is crucial, with Sal and Seesham being the traditional choices, though Gular wood is now the most commonly used. Before carving, the wood undergoes a slow heating process to remove moisture, ensuring durability. Tiny birds and animals are skillfully carved from a single piece of wood, ranging in size from half an inch to four inches, and assembled using nails and glue. The carving process involves peeling, shaping, and detailing with knives and simple tools. Once shaped, the toys are passed on to painters who add vibrant colours and intricate patterns. A final coat of lacquer is applied to enhance the shine and finish.

4. Chikankari of Lucknow

Chikankari, a delicate and intricate embroidery form, has its roots in Persian craftsmanship, with the word Chikan meaning "making delicate patterns on fabric." Inspired by Turkish embroidery, it was introduced to India by Mughal Empress Noorjehan in the 17th century and flourished under the Mughal patronage. However, its earliest references date back even further, with Greek traveller Megasthenes mentioning Indians wearing flowered muslins as early as the 3rd century B.C. Traditionally, Chikankari is a subtle white-on-white embroidery where delicate stitches create beautiful textural contrasts, shadows, and traceries. Unique variations like Anokhi Chikan ensure that the stitches remain invisible from the back, showcasing the finesse of the craft. The process involves multiple stages—cutting, stitching, block printing, embroidery, washing, and finishing—each carried out by different sets of artisans. Wooden blocks dipped in dye imprint intricate patterns onto fabric, which is then embroidered by skilled craftsmen specializing in different stitches. These stitches fall into three main categories: Flat stitches (Taipchi, Pashni, Bakhia, Dhoom), Embossed stitches (Murri, Pahanda), and Jaali work (Siddhaur, Bulbul), each lending a distinct texture to the fabric. Embroidery is done on light muslins and cotton in soft pastels, though modern adaptations now feature coloured and silk threads to match contemporary fashion trends. Frames are used to maintain fabric tension, ensuring uniformity in stitches. The final and crucial stage is washing, which reveals the true essence of the embroidery. Today, Lucknow is the heart of the Chikankari industry, with Lucknawi Chikan being revered for its elegance and craftsmanship, keeping this centuries-old tradition alive in the world of fashion.

5. Carpets of Mirzapur

Mirzapur, a major hub of carpet weaving in Uttar Pradesh, has a rich history that dates back to the Mughal era and was later industrialized by the British. Locally known as Galicha, these carpets are woven primarily by the Bind community and other artisans listed under the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category. The region plays a dominant role in India's carpet industry, contributing nearly 47% of the national production, as noted in the 2020 All India Handloom Census. Workshops in villages like Purjagir, Mujehara range from long, narrow spaces housing large iron looms for multiple weavers to small looms set up within homes, where entire families participate in the craft.

The most traditional technique, knotted weaving or tapka, involves manually tying woolen stitches on a cotton frame. Each knot consists of a charri (line stitch) made with wool, secured with lachhi (U-shaped cotton loops). The weaver brings the thread forward, cuts it with a chura (small knife), and then taps the entire line using a panja (iron comb) to ensure tightness. The repetitive cycle of squatting, knotting, and tapping is physically demanding, requiring artisans to frequently adjust the sut (cotton frame) with a dambh (bamboo lever). In contrast, tufted weaving, a modern adaptation, uses a handheld machine for embroidery, making the process easier but reducing the intricacy of traditional techniques.

A special type of carpet, Soumak, is a single-coloured Galicha with a uniform design, preferred by weavers with smaller looms. Due to lower wages—Rs. 200-350 per day—many weavers have shifted to tufted weaving, while others have abandoned the craft altogether.

6. Attar of Kannauj

Attar is a natural oil derived from the hydro-distillation of rose (gulab), vetiver (khas), screwpine (kewda), tuberose (rajnigandha), and Arabian jasmine (bela), etc. (Handa et al., 2008). Some of the prominent ittar producing sites in India are Kannauj, Gazipur, Jaunpur, Vijaywada, Saluru, Mysore and Ganjam (Kapoor, 1991; Rao & Rout, 2003). Kannauj or the ‘Ittar Nagri’ (Perfume City), is the most prominent among these centers and has been in existence since the Vardhana dynasty of the 7th century (Padhy et al., 2016). Situated on the banks of river Ganges, Kannauj is blessed with fertile alluvial soils, ideal for the cultivation of Damask rose, jasmine, mehendi (henna or Lawsonia inermis) and bela (Arabian Jasmine). Recognising the heritage of ittar making at Kannauj, the Government of India awarded it with the Geographical Indicator (GI) label in 2014 (MSME Report, 2016–17). Presently, it is classified as ‘Ittar and Essential Oil Cluster’ under the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) and the state government has attempted to bolster the industry by recognising it under the ‘One District One Product’ (ODOP) scheme. The stature of Kannauj in ittar mak-ing is comparable to that of Grasse in France and the National Geographic Magazine lauds it by recognising: ‘perfumers in Kannauj have worked their alchemy to create liquid gold’ (Sachasinh, 2021).

Ittar is a natural oil derived from the hydro-distillation of rose (gulab), vetiver (khas), screwpine (kewda), tuberose (rajnigandha), and Arabian jasmine (bela), etc. (Handa et al., 2008). Some of the prominent ittar producing sites in India are Kannauj, Gazipur, Jaunpur, Vijaywada, Saluru, Mysore and Ganjam (Kapoor, 1991; Rao & Rout, 2003). Kannauj or the ‘Ittar Nagri’ (Perfume City), is the most prominent among these centers and has been in existence since the Vardhana dynasty of the 7th century (Padhy et al., 2016). Situated on the banks of river Ganges, Kannauj is blessed with fertile alluvial soils, ideal for the cultivation of Damask rose, jasmine, mehendi (henna or Lawsonia inermis) and bela (Arabian Jasmine). Recognising the heritage of ittar making at Kannauj, the Government of India awarded it with the Geographical Indicator (GI) label in 2014 (MSME Report, 2016–17). Presently, it is classified as ‘Ittar and Essential Oil Cluster’ under the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSME) and the state government has attempted to bolster the industry by recognising it under the ‘One District One Product’ (ODOP) scheme. The stature of Kannauj in ittar mak-ing is comparable to that of Grasse in France and the National Geographic Magazine lauds it by recognising: ‘perfumers in Kannauj have worked their alchemy to create liquid gold’ (Sachasinh, 2021).

Kannauj, often called “Ittar Nagri “ (the city of perfume), has been the heart of attar production since the 7th century, tracing its roots back to the Vardhana dynasty. Located on the fertile banks of the Ganges, its rich alluvial soil provides ideal conditions for cultivating fragrant flowers such as damask rose (gulab), jasmine (bela), vetiver (khas), tuberose (rajnigandha), and screwpine (kewda). Nearly one-third of Kannauj’s population is engaged in the attar-making industry, which thrives as a traditional cottage enterprise with around 300 registered distillation units producing attars worth nearly Rs. 1,000 crores annually.

The age-old deg-bhapka method of hydro-distillation remains the backbone of attar production in Kannauj. This process captures the essence of flowers and herbs by distilling their fragrance into sandalwood oil, which acts as a fixative. Some attars, like Chhoya/Nakh Chhoya, are obtained through dry distillation, producing deeply aromatic extracts such as loban. Traditionally, attars were stored in leather bottles, which, through osmosis, helped remove excess water content, enhancing their purity and longevity. In addition to being used as perfumes, attars were historically valued for their medicinal properties, often prepared by vaids and hakims for therapeutic use. Recognized for its heritage and craftsmanship, Kannauj attar received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2014, cementing its status as a cultural and aromatic treasure of India.

7. Khurja Pottery

Khurja, a small town in Uttar Pradesh, is famous for its unique pottery and is often called “The Ceramic Town of India”. With nearly 400 pottery factories, it has become a major hub for ceramic production. Unlike traditional pottery made from regular clay, Khurja Pottery is crafted using a mix of clay, feldspar, and quartz. These minerals give the pottery a natural shine even before it is shaped.

Khurja Pottery is India’s oldest form of glazed pottery, easily recognized by its beautiful floral patterns in blue or brown on an off-white background. The craft has evolved over time—from simple red clay pottery to blue-glazed designs and red clay engravings with delicate white floral motifs.

The history of this craft dates back over 600 years. Some believe that potters from Egypt and Syria brought their skills to Khurja when they traveled with Afghan King Taimur Lung. Others trace its roots to the Mughal period, during the reign of Mohammad-bin-Tughlak in the 14th century. Another theory suggests that artisans known as Multani Kumhars migrated from Multan and settled in Khurja, bringing their pottery-making traditions with them.

Today, the industry employs around 25,000 workers, with many more involved in related activities. Khurja mainly produces whiteware, but some units also manufacture terracotta items for export. The town is known for making crockery, decorative items, and even industrial products like electrical insulators and sanitary ware.

8. Glass work of Firozabad

Firozabad, a city in western Uttar Pradesh, has been a hub for glass forming and shaping for generations. Almost every family in the region is connected to this craft, making it an essential part of their cultural heritage. The city specializes in Glass Flamework, also known as Torch or Lamp work, practiced using borosilicate and soda-lime glass. Both Hindus and Muslims engage in this craft, adding to its diversity. Flameworking is a technique where glass is melted using a flame from a burner (torch or lamp), powered by LPG gas and oxygen. Once molten, the glass is blown, shaped, and formed using various tools. Although its origins are unclear, the earliest evidence of flameworked glass dates back to Mesopotamia in 2700-2600 BC. In Firozabad, artisans create a wide range of decorative and utility products, including idols, jewelry, hookahs, bongs, paperweights, pens, door handles, and bells. The demand for hookahs, bongs, and smoking pipes in the international market helps sustain the craft. Artisans specialize in different techniques such as hollow glass work, solid glass work, lathe machine work, and bead making. Many have shifted from soda-lime glass to borosilicate glass due to its durability, safety, and ease of use. Firozabad’s well-known glass clusters can be found in Suhag Nagar, Raja Ka Taal Kheda, Potla Chungi, and Station Road, keeping this ancient tradition alive.

9. Woodwork of Saharanpur

Saharanpur, popularly known as the ‘Sheesham Wood Village,’ is renowned for its exquisite woodwork and intricate craftsmanship. The city's legacy dates back to the 13th century when it was named after the Sufi saint Shah Harun Chishti. Over time, it has become a hub for skilled woodcarvers, producing a vast range of handcrafted products. Various types of wood are used—sheesham for smaller items, teakwood for furniture, and mango wood for antique-style pieces. Despite the diversity of products, the fundamental crafting process remains the same, involving slicing, carving, inlaying, sanding, polishing, and assembling. Each artisan, or karigar, specializes in one or more of these steps, making every piece a collective effort of multiple craftsmen. The traditional product range includes ornately carved furniture such as sofa sets, chairs, tables, stools, and wall brackets, along with decorative screens, tableware, mirror frames, bookshelves, and children’s toys. In recent years, artisans have been experimenting with new materials and innovative designs to expand their offerings while keeping the essence of their craftsmanship alive.

10. Zardozi embroidery of Lucknow

In the dim glow of an old workshop in Lucknow, nimble fingers dance over velvet stretched tight on a wooden frame. Gold and silver threads through the fabric, forming intricate patterns fit for a king. This is Zardozi, an art once reserved for royalty, now carried forward by artisans who stitch stories into every thread. The name Zardozi comes from zar (gold) and dozi (embroidery), reflecting its royal origins. During Aurangzeb’s reign in the 12th century, Lucknow became the main center for this intricate art, with skilled artisans creating luxurious designs for the nobility.

Originally, Zardozi was embroidered with pure gold and silver threads, but today, artisans use copper wires coated in gold or silver polish, along with silk threads. The embroidery is done on rich fabrics like velvet and satin, stretched over a wooden frame called an adda. The work is further embellished with materials like dabka (coiled threads), kora, katori, tikena, and sitara (sequins), adding texture and shine. Also known as Karchobi, Zardozi is used not only on clothing such as sherwanis, sarees, and jackets but also on accessories like handbags, belts, and shoes, as well as home décor items like cushion covers and curtains. While traditional designs featured floral and leaf motifs, modern variations incorporate geometric patterns.

Lucknow remains a hub for this craft, preserving its heritage while adapting to contemporary styles. Today, artisans continue to create stunning Zardozi embroidery, keeping alive a tradition once reserved for royalty.

Leave a Comment