- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Gaatha

- Product Code: 3760-JAN20-MFG-2

- Weight: 250.00g

- Dimensions: 15.00cm x 20.00cm x 25.00cm

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

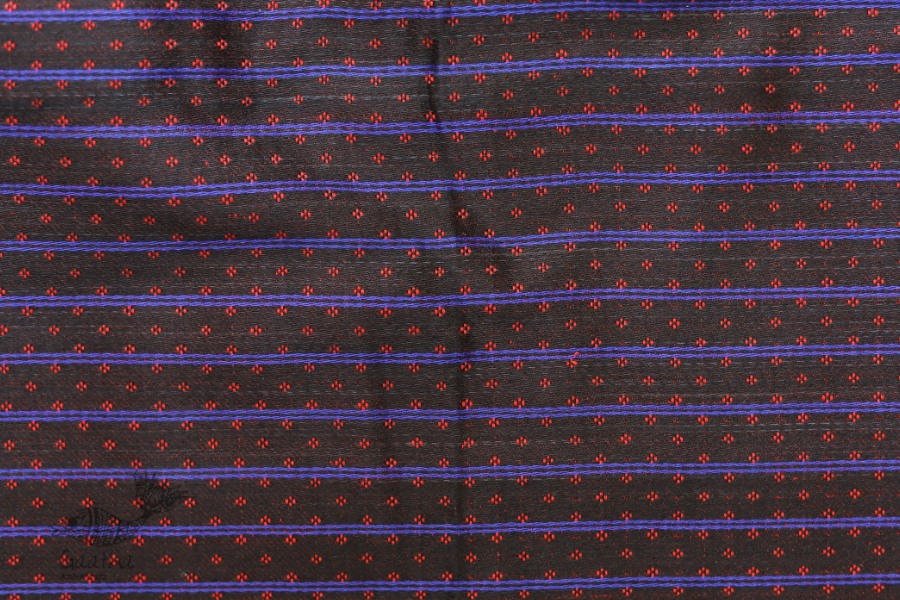

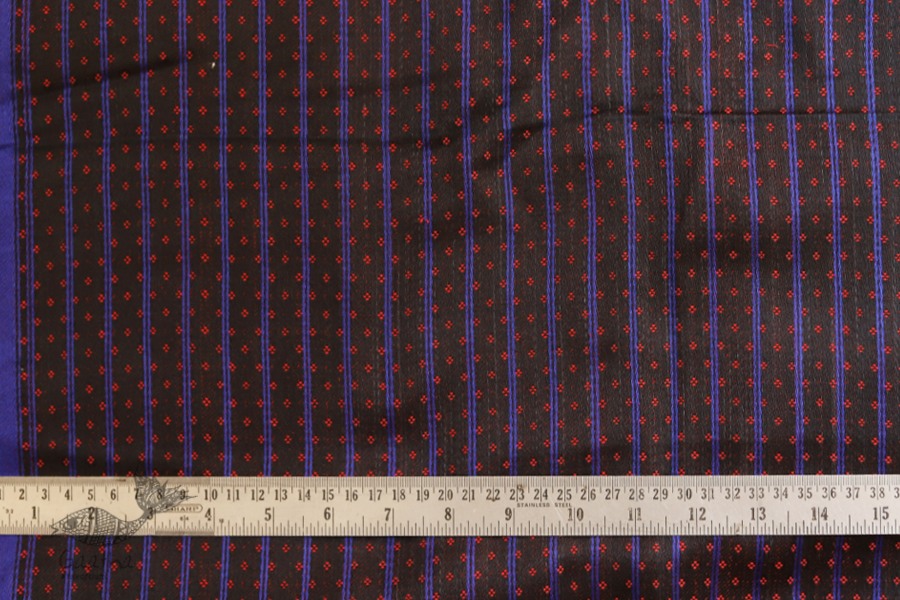

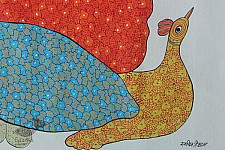

It is not just kaleidoscopic embroideries that Gujarat is so famous for; it is also the home of wonderful weaves that combine impressive skill and generations of expertise, with the result of pure aesthetic joy. Reaffirming that appearances are deceptive, the spectacular Mashru has the appearance of glistening silk that conceals the soothing feel of cotton.

Mashru has characteristic bright contrasting stripes in vibrant colours, instantly uplifting the spirits of a desert traveler. It seems that to make up for the lack of colour in the dry barren deserts, the makers of this fabric put every possible colour together in wonderful, lustrous compositions.

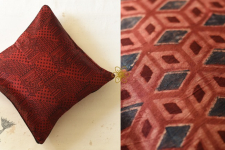

Blending the opulence of silk and the comfort of cotton, this magic fabric in its multicoloured stripes and ikat patterns has been a favourite among those with a taste for luxury. Mashru is not just a luxurious fabric; it also has a very practical utility. While the silk on the outer surface has a beautiful, glossy appearance, the cotton yarns in the back soak up sweat and keep the wearer cool in the hot climate of the deserts.

Mashru weaving is an old tradition in India and this textile was traded to Arabian countries. Mashru means “permitted” in Arabic and it is believed that this textile got this name when Muslim men, who were not allowed to wear silk, started wearing this fabric. Since the body is in contact with cotton and silk is only the exterior, they got approval to wear this luxurious fabric. Slowly, it became liked by Hindus also and these days, this fabric can be seen in the clothes of Kutchi nomads.

While the small dotted pattern is preferred in Anjar, Kutch, the striped ones are liked all over the country. Traditionally used in garments, Mashru is also used for making quilts, cushions and bags. The craftsmen have also developed new designs, by tie-dyeing the fabric using ‘Bandhani’ technique.

Mashru fabric is made using satin weave by interlacing silk and cotton yarns. Cotton makes the weft, or the horizontal yarns while silk is used for the warp, or the vertical yarns. In this weave, each silk yarn goes under one cotton yarn and above five or eight or more cotton yarns, giving an appearance of a shiny surface that looks like it is made up of only silk, while the underside of the fabric is cotton. Since the structure of the fabric allows for more yarns in a given area, it also makes the fabric stronger.

With time, the designs of Mashru have become simpler. Multi hued ikats and patterned stripes are uncommon now, and replacing them are brighter, bold stripes or small dots, along with solid coloured fabrics.

The weaving of this fabric was practiced across the country in different forms; from Deccan to Bengal, now it is only done in Patan and Mandavi in Gujarat.

In a small locality in Patan, Gujarat, a few craftsmen weave Mashru yardages, replacing vegetable dyed silk with chemical dyed rayon, not because they don’t want to use silk, but because rayon, being cheaper, has a better demand. Rayon is smoother and shinier than silk, although the synthetic dyes make it weak, unlike natural ones that grow richer with age.

These expert weavers, who learnt and carried on this exquisite craft from their ancestors, are probably the last generation who will be practicing this craft. Now in their 60’s, they work in their homes for eight hours a day, while their children venture out into bigger cities for lucrative and stable jobs.

This precious fabric finds customers all across the country and is also exported; and like Mashru’s colours cheer up a tired soul, the popularity of this multi hued textile among colour loving youth keeps the hope of revival of this beautiful craft.

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Mashru: Craftsmen at Patan |

| Village | Patan, Ahmedabad (Gujarat) |

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | ♦ The items in this category are non-refundable & non-returnable. ♦ The product is only eligible for a refund or exchange in the case of damage or defect. ♦ The products in this category are handmade. |

| Material | |

| Made of | Silk + Cotton |

| Instruction | |

| About Sizes | 100 X 55 CM |

| Note | As each piece is hand printed and unique, expect some variation from shown design. These might slightly differ from as seen on digital screen. |

-225x150w.jpg)

-1-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

/25_12_2020/13-(1)-225x150h.jpg)

/25_12_2020/13-(2)-225x150.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-250x250w.jpg)

-250x250.jpg)

-250x250.jpg)