- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: kartik chahan (Fine Design)

- Product Code: 4005-KPC20-20

- Weight: 700.00g

- Dimensions: 30.00cm x 30.00cm x 15.00cm

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

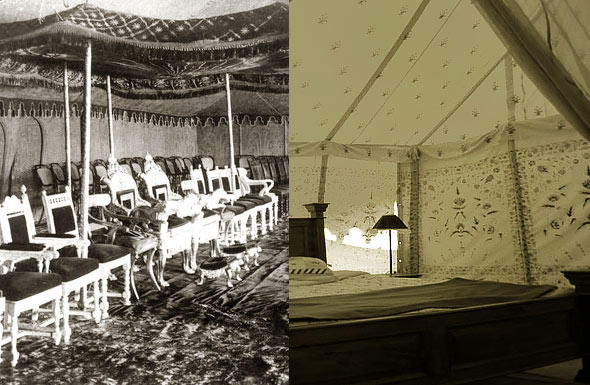

A camp in a desert or a hunting expedition in the middle of a forest or a battle field, something that stayed with the kings of the western India irrespective of the situation they were in is luxury. This was the kind of luxury that spoke through exclusivity and fine craftsmanship. Whether it was their serve ware embellished with precious stones, silk robes embroidered with gold zari or their canvas camps worked with finely stitched fabric pieces of colorful silk and cotton. These Camps were hand made by the local women of the community with the technique called Katab, popularly known as appliqué these days.

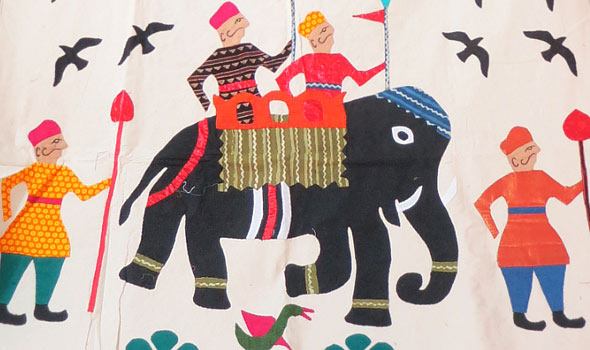

Origin of appliqué can be identified by the style of fabrication, color usage, composition and the kind of forms of patterns used. History of Appliqué work in India can be traced as back as the times when the women folk of the native communities of north Gujarat; the Kathis (the land owners), the Mahajans (the businessmen), the Rabaris (the nomad camel herders) and the Muslims produced large canopies, hangings, friezes, bullock-covers (Jhul), tents for ox-carts with human and animal figures stitched on them.

Some of the old examples of this craft are full of patchwork with cotton and silk, Bandhani and Mashru fabrics, covered with exuberant imaginative forms, both symmetrical and asymmetrical. Quite often the appliqué technique was accompanied by range of stitches adding more value by increase the visual depth and surface richness. Another method known by the name of ‘Reverse appliqué’ in which cut work in the surface fabric forms the shape was also explored. The color palette of appliqué artists of Gujarat varies from warm to cool, white on white, bright and festive to natural and neutral tones today.

Hirabhai Chauhan’s family along with many others migrated from Sindh (Paskistan) to Jamnagar in 1946 during the India-Pakistan partition. They brought with them almost nothing except for the ancient craft of applique work that their forefathers had taught them. In Jamnagar some took to weaving dhablas (coarse woolen shawls) and Tangalias (skirt pieces) for the local Bharwad community, while others took to working as laborers in farmlands and construction sites. Unable to make a living in Jamnagar, some of Hirabhai’s family moved to Ahmedabad, where they lived in a tiny, tin roof house and he started working as a tailor. The women however, with the leftovers of tailor shop continued making applique quilts, Chandarvos (wedding decorations), Torans (embellishment for entrance of the house), Dharamyas and other decorative items for their homes and cattle. And it was this secondary occupation that brought a ray of light to the family struggling to meet ends at that time.

In 1978, they got their first big order from Gujarat State Handicrafts and Handloom Development Corporation, to replicate their museum collection pieces. Thereafter there has been no looking back for them. They are training low income group women in the craft and have been able to help 1200 – 1500 women across four clusters including Baroda, Rajkot & Ahmedabad Today, they even work with some of the top designers of the country to develop products for them.

The craft consisted of cutting intricate floral, animal and geometrical patterns in fabric that are then sewn together by hand. Muslin, which is used as the base material is procured from Ahmedabad. Thick count fabric for a strong and durable base and a thinner count for the upper layer, which is to be cut and stitched together are chosen. These are cut in the size of 16” x 16” panels for work ease. Desired patterns are either individually cut on the thinner fabric (in case it is a new design) or they are stacked together, starched and ironed to make them crisp and then cut together in a stack, running a rolling blade tool over the entire stack. These layers are then separated and sandwiched with the thick count muslin at the base and distributed amongst the women.

These individual square panels are then joined together to make bed sheets, cushion covers, curtains, table runners, dress material etc. More than a hundred designs, tessellated to form so many patterns. Mirror work with tiny round mirrors embedded in the white applique work gives it a breath taking appeal.

Working since 50 years in the craft of applique work, a major turn in the way they were combining fabrics to create applique masterpieces came when a buyer insisted on turning it all white. Their white on white applique were much appreciated all over the world and appealed to a large sector of people with taste for subtlety. ‘Godadi’, thick covers for winters out of all other products made originally are the most popular ones. Flaunting the dexterity of a pair of skilled hands, small abstract patterns of applique adorning a garment or animal motifs with trees enhancing home furnishing have tickled our curious nerve since time immemorial and will continue doing so.

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Shri kartik chahan |

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | The items in this category are non refundable but you may exchange this product with any other product from the same category. The products in this category is handmade. The product is only eligible for a refund in the case of damage or defect. |

| Material | |

| Made of | 100% Cotton |

| Instruction | |

| About Sizes | 15.7" x 15.7" |

| Note | As the product is handmade and every piece is unique, expect minute variation from shown design and shape. |

/25_12_2020/Applique-Kaam-⌘-Cushion-Cover-⌘-20.jpg)

/25_12_2020/20-(2).jpg)

/25_12_2020/Applique-Kaam-⌘-Cushion-Cover-⌘-20-80x80w.jpg)

/25_12_2020/20-(2)-80x80w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

/25_12_2020/Applique-Kaam-⌘-Cushion-Cover-⌘-20-250x250w.jpg)

/25_12_2020/20-(2)-250x250w.jpg)

-250x250.jpg)

-250x250.jpg)