Taamr . ताम्र - Brass - Davara Coffee Set

- Availability: Out Of Stock

- Made & Mkt by: Coppre

- Product Code: 4018-C22-S50-12

- Weight: 500.00g

- Dimensions: 15.00cm x 15.00cm x 10.00cm

Rs.1,400

Savour the goodness of South Indian Filter Coffee in our handcrafted pure brass filter coffee set. Filter coffee is typically drunk from a cup-saucer combination called the Davara tumbler. The rim on the tumbler enables a dip-free pouring from tumbler to saucer for temperature moderation. Till date, filter coffee is drunk from this cup-saucer duo in most South Indian homes. The Davara tumbler is a cultural and heritage marker. Reminiscent of the times when the elders in the family started the day with a cup of coffee and a newspaper to read. Our Davara tumbler filter coffee set retains the vintage design, with a few design tweaks. Indulge us in some coffee gyaan while we are at it. Coffee is not a native drink of India and was brought to India, like tea. But did you know Coffee came to India well before the East India company? It is believed that an Indian Sufi saint named "Baba Budan" introduced the coffee plant to India by bringing seven raw beans while returning from Hajj and planted it on the hills of Chikmagalur, Karnataka in 1670. Ever since coffee has become a ritual in homes across the country.

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

9328006304 ( WhatsApp )

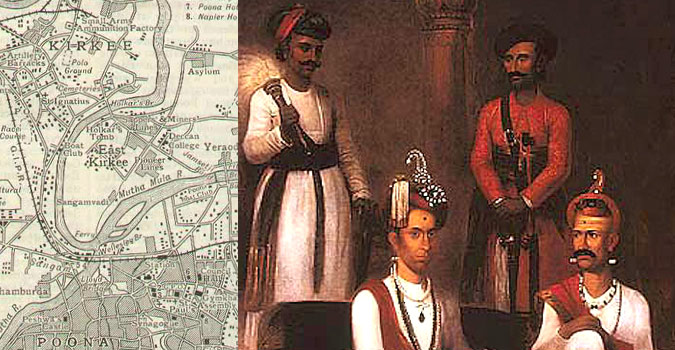

The legacy of the Tambat Craftspeople who handcraft Coppre's products dates to the 17th century when they were invited to Pune by the Peshwas when Shivaji set up the city as the capital city of the Maratha Empire.

When the Tambat craftspeople migrated from Konkan to Pune, they formed their settlement in Kasba Peth, an already established nucleus of old Pune. Their precincts came to be known as Tambat Ali (Ali:precincts). These narrow and dusty alleys of Tambat Ali where the timeless sound of metal-hammers clang on copper, have remained pretty much the same as they were almost 300 years ago.

From making armour, coins, canons, copper utensils, ritual wares for the Peshwa rulers, the Craftspeople embraced the culinary and ritual needs of Maharashtrian communities and crafted traditional products such as utensils and puja items.Distinguishing feature of Tambat craft

‘Matharkaam’ or beaten work is the distinguishing feature of Tambat craft. The hand-beaten indentations, made by profiled beating hammers, strengthen the object and enhance the inherent rich surface by imparting a mirror-like appearance. It is a skill intensive craft and needs strength, dexterity and a keen hand-foot-eye coordination.

It is the only skill that the community could save from the onslaught of mechanization with the coming of British rule, which to date has not leant itself to be mimicked on any machine.

The loss of the patronage of the Peshwas, the introduction of mechanization and the bans imposed by the British, forced the Tambats to set up their own shops to sell their wares to the commoners. Over the years, the members of the Tambat community practicing this craft have continued to dwindle. There were upto 800 Tambat households in the early 1970s. By the early 90s, The Tambat households in Pune city fell to 250. Currently, about 80-100 families directly depend on the Tambat Craft for their livelihood.

Hit by changing traditions, rising copper prices on the commodity markets in recent years, the convenience offered by materials like stainless steel and plastic and the provocative economic opportunities outside the confines of their craft, has led to a near stagnation. Yet some families of the community persevere with this craft of shaping objects from sheets of copper they carry on the ghadkaam (raising, sinking and shaping of the utensil), the crafting of ritual wares, nakshikaam (repousse and chasing); and the crafting of one-off temple objects.

Passed on through apprenticeship from one generation to the next, today the craft remains in the hands of a few craftspeople with even fewer willing to take on this heritage craft.

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Artisan working with coppre |

| City | Pune, Maharashtra |

| Shipping ~ | |

| Shipping | 7 to 6 working days, |

| Material | |

| Made of | Brass |

| Instruction | |

| About Sizes | Dimension: 4'' dia x 3.2'' ht | Weight: 189 gms |

| Care | Your uncoated products should be washed daily with a soft cloth and a detergent/metal cleaning agent. Wipe dry immediately after washing. It is important to wipe away all traces of water after washing, else the carafe will catch water stains. Washing and wiping on a daily basis will help retain the coppery shine on your product and will also prevent the build-up from the natural oxidation process of copper when it is exposed to the atmosphere. |

| Restrictions | |

| COD - Option | Not Available |

A camp in a desert or a hunting expedition in the middle of a forest or a battle field, something that stayed with the kings of the western India irre..

Rs.4,250

A camp in a desert or a hunting expedition in the middle of a forest or a battle field, something that stayed with the kings of the western India irre..

Rs.4,250

A camp in a desert or a hunting expedition in the middle of a forest or a battle field, something that stayed with the kings of the western India irre..

Rs.4,250

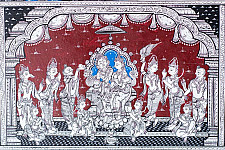

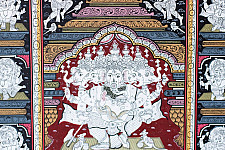

Misty daybreak and the first calls of the rooster in a scenic village have the men going to the river for ablutions, preparing themselves for a day fi..

Rs.458,500

Misty daybreak and the first calls of the rooster in a scenic village have the men going to the river for ablutions, preparing themselves for a day fi..

Rs.78,600

Misty daybreak and the first calls of the rooster in a scenic village have the men going to the river for ablutions, preparing themselves for a day fi..

Rs.59,000

Misty daybreak and the first calls of the rooster in a scenic village have the men going to the river for ablutions, preparing themselves for a day fi..

Rs.52,500

The demure look of the eyes and the colorful exuberance of the costumes of a new bride amidst the Kutch lands are finely balanced with layer..

Rs.2,450

Some wandering rays of an aimless light, Carelessly slipped into my loom the previous night… Their whimsical sparks got woven away, Within the mortal ..

Rs.23,850

It is not just kaleidoscopic embroideries that Gujarat is so famous for; it is also the home of wonderful weaves that combine impressive skill and gen..

Rs.475

Strolling by the ghats of Banaras stimulates all senses. One may see vivid and bright colours rushing towards the holy river- saints draped in orange ..

Rs.2,999

She finishes the bedtime story and tucks him in his bed. Ready to sleep, she leans forward to give him a goodnight kiss. As she is about to get up, sh..

Rs.1,550 Rs.2,500

Music, they say, is the silence between two notes. The silence becomes even more omnipresent as it makes rare appearances between the constant sounds ..

Rs.10,500

Gathering commences in the middle of deserted pavilions where velvet carpets adorn the Dessert lands & Manganiyars play folk music as a bugle for ..

Rs.512 Rs.1,025

Gathering commences in the middle of deserted pavilions where velvet carpets adorn the Dessert lands & Manganiyars play folk music as a bugle for ..

Rs.512 Rs.1,025

Gathering commences in the middle of deserted pavilions where velvet carpets adorn the Dessert lands & Manganiyars play folk music as a bugle for ..

Rs.512 Rs.1,025

Gathering commences in the middle of deserted pavilions where velvet carpets adorn the Dessert lands & Manganiyars play folk music as a bugle for ..

Rs.512 Rs.1,025

A familiar chatter swells in the air as feet chase the trail of a carelessly flying odhani in the by-lanes of Bhuj, spilling colors all over. While&nb..

Rs.3,070 Rs.3,412

A familiar chatter swells in the air as feet chase the trail of a carelessly flying odhani in the by-lanes of Bhuj, spilling colors all over. While&nb..

Rs.9,310 Rs.10,345

A familiar chatter swells in the air as feet chase the trail of a carelessly flying odhani in the by-lanes of Bhuj, spilling colors all over. While&nb..

Rs.3,460 Rs.3,845

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)