- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Kirit Jayantibhai

- Product Code: 0303-DP21-04

- Weight: 1,600.00g

- Dimensions: 35.00cm x 33.00cm x 6.00cm

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

9328006304 ( WhatsApp )

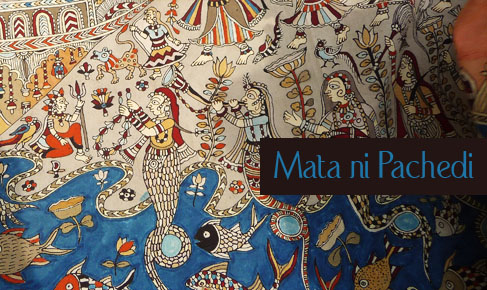

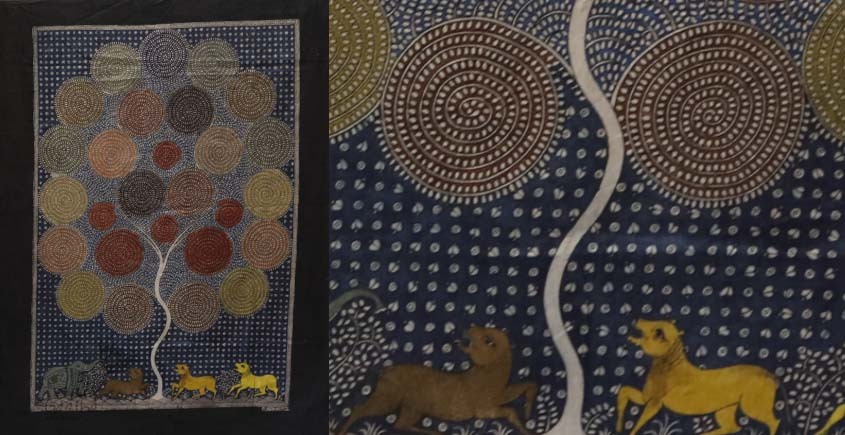

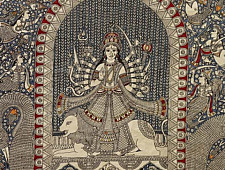

Red… the colour of blood, of life, vitality… red, the colour of the Mother Goddess, the embodiment of power, the nurturer and destroyer… the protector of the weak. In a great battle between Shiva and the asura (demon), Raktabija, every drop of the asura’s blood that fell to the earth, gave rise to more and more demons. The gods then turned to Shakti, the goddess Durga, to annihilate the asuras. The fierce goddess pierced the demon’s body and drank all his blood, thus saving both the worlds. The goddess in her seven forms is now worshipped during the nine days of Navaratri festival.

Mata ni pachedi literally means “behind the mother goddess”, and is a cloth that constitutes a temple of the goddess. When people of the nomadic Devi Poojak community of Gujarat were barred from entering temples, they made their own shrines with depictions of the Mother Goddess on cloth. This ingenuous solution is believed to be the origin of Mata ni Pachedi, the sacred art, which is now revered by all. Whether it is the richly decorated with gold Pichwai paintings of Nathdwara, or the folk art of Mata ni Pachedi, Hindus have always decorated their temples and shrines with narrative illustrations that depict stories of the gods and goddesses.

Traditionally, red is the main colour of the paintings, the sacred red that punctuates every auspicious occasion in the life of a Hindu. White and black form the backdrop for the brilliant red. Using just these three colours, the imaginative artists depict entire stories laden with numerous characters and motifs. The painting usually has a set pattern, with the mother Goddess dominating the central area in her mighty form, surrounded by deities and commoners worshipping her with equal reverence. Mata ni Pachedi is also known as the “Kalamkari of Gujarat”, owing to its similarity of the Kalamkari practiced in Southern India and the use of pens(kalam) fashioned out of bamboo sticks, for painting. To quicken the process and meet demands of villagers, who would commission paintings to offer to the mother goddess on fulfillment of wishes, the painters started using mud blocks for printing. These blocks were large and coarse, and after using a few times, would be thrown in the river where they returned to the soil. Over the course of time, wooden blocks replaced mud blocks, facilitating the use of finer motifs. Yet, the craftsmen still often make the entire painting with the bamboo “kalam”, using blocks only for printing the borders.

In a small locality in Ahmedabad, artisans make these paintings using the same methods followed 200 years ago. Cotton fabric is first de-starched and then treated with Harada paste, to prepare it for absorbing the colour. Outlines of the figures are painted first, with black colour prepared from jaggery and iron. After this, red colour, extracted from tamarind seeds, is filled in and the areas supposed to be white are left blank. After application of each colour, the fabric is boiled in alizarin solution, to bring out the colour, and then washed. For washing, the craftsmen go to Sabarmati River as the cloth must be washed in running water only, so that any excess colour flows away, instead of staining the cloth.

It takes days of patience and dedication, to prepare one piece of this beautiful folk art. For instance, painting a cloth of 5” x 9” can take two months. The artists get a rush of orders a couple of months before the Navaratri festival. The strong lines and bold use of colour, that reflect the power and energy of the goddess, have now transformed to more artistic and detailed illustrations; but the depiction style of mythical characters remains the same. The artists now incorporate many more colours such as indigo, green and yellow in the paintings, using the age old methods of extracting colour from natural materials. They use their skills to make smaller souvenir pieces for the fascinated visitor, and also make products like wall hangings and stoles, using newer motifs.

While craftsmen are refining this folk craft to suit the changing times, yet the sanctity of this religious artifact remains untouched. Creating Pachedis as well as new illustrations that are relevant in today’s context, but in the same folk style, these craftsmen have remained true to the cause of spreading the glory of the Mother Goddess and her wonderful art.

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Kirit Jayantibhai Chitara |

| City | Ahmedabad |

| Details | |

| Product details | This painting is a folk art by craftsmen from a nomadic tribe. It is not a fine art product, hence, certain imperfections or initial strokes of the first draft are visible and this only adds to the raw look of the artwork. |

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | The items in this category are non refundable. The products in this category is handpainted. |

| Material | |

| Made of | Hand painted on Cotton base (Madar Pat) with Natural color pigments. |

| Instruction | |

| Note | These paintings are hand-made, naturally dyed and unique, these may differ ( Color & Form ) slightly from the snaps seen on digital screen. -The paintings will be shipped in folded form & without Frame. -We would suggest the buyers to frame these paintings with caution. This Mata ni Pachedi painting is on 'Made to Order' basis. It will take 45-50 days to be delivered once the confirmed order is placed. |

| Restrictions | |

| COD - Option | Not Available |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-225x170w.jpg)

-225x170h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

/06_05_2024/Padmapriya-Handwoven-Chanderi-Full-Jaal-Pink-Saree-225x150h.jpg)

/06_05_2024/13-(1)-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-copy-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-234x234h.jpg)

-234x234w.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)