- Availability: 4

- Made & Mkt by: Gaatha

- Product Code: 4031-CM-12

- Weight: 500.00g

- Dimensions: 7.50in x 6.00in x 0.00in

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

9328006304 ( WhatsApp )

The lush earth , in an embrace with fabric, sprouts beautiful patterns. And the earth had it’s playful ways, in slowly letting out this secret, to the Rangrez.

It had clung onto his dhoti a day back at the riverside. He was deep in thought now, as he gathered the fabrics to be dyed. The dhoti went along with the rest of the clothes, in the swift sweep of his hands and straight into the Indigo vat. He was surprised to find an odd-one-out the next day, amongst the dyed fabrics, left out to dry. The parts where the earth rested, the dye did not blot on. That part had retained the original colour, like stars in an indigo sky. This way, the earth confided a crumb of it’s mystery, to the Rangrez. And then on, they conversed in patterns.

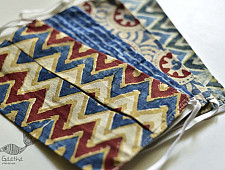

This is one of the many stories of the origin of Dabu or Mud- resist printing. Like the craft, the raw materials too are timeless - mud and water. Replenished generously by nature, these are believed to have been employed in India, during 8th century AD. This is indicated by the oldest specimen found of Dabu printed fabric in Central Asia. The prints popularly adorned the flowing Ghagras. These were the favored clothing of the women, locally called ‘Fetiya’ in Rajasthan. This was usually coupled with a Bandhej Lugda (a long fabric draped over the head).

Taking one long Dabu printed fabric with the preferred motifs of concerned community, Fetiya was made with just one line of stitching. It was crafted by joining the extreme ends of a 8-12 meter fabric (the length varied with the buyer's interest). The garment then beautifully enveloped Jat, Gadariya & Gujjar women.

The patterns are traditional, handed down intact, over generations. The motifs are picked from nature and surrounding elements, and then crafted onto wooden blocks. Popular ones are Kahma, Lal titri, Dholika, Kantedar. The craftsmen dip the blocks into a viscous paste of mud, gum and lime. The method gets it’s name from the word ‘dabaana’ , meaning ‘to press’.

Earlier, Rajasthan province was densely peppered with Dabu printing clusters. Now, very few remain to live the legacy. One of the few clusters is the Akola village, which thrives solely on the fabric demands of neighboring villages. The colors of the sky - blue of the day, indigo of the night, red of the sunsets - are mostly seen in the regional attire. The village is a self sufficient system for Dabu printing. Block carvers sculpt the blocks, the earth lends mud and the river bestows water. The fabrics are sourced from Kishangarh and pigments come from Udaipur.

Their craft speaks of skill and years of experience, as the craftsmen swiftly pattern the clothes. The application of resist and dye are done several times, painstakingly with great artistry, to get various shades of ground and motif color. As time passed, Alizarin pigment used to impart red color was replaced by Naphthol and the craftsmen began to use tar instead of mud in case of designs which require sharper contrasts

.

As told by Master craftsman Gopal Bhai, the native craftsmen known as Chippas, specialize in block printing. Few hundred years ago, Rani Rathorji of Mewar, established a village by the banks of Beduch river for them. Today around 200 people practice this craft in this quaint village.

Like the essence of earth, Dabu prints remain the primeval printing method. The prints are now popularly known as Akola Dabu prints. And like the patterns , these fabrics are deeply embedded in the cultural identities of various Rajasthani communities. The forms in which these fabrics are worn are changing with time, organizations like Aavaran and COS-V are giving new direction to this unique craft, yet the soul of the craft is carried forward, untampered, by the motifs and hues. Stories of the earth and dye, rest safely in hands of the craftsmen. Do you hear them?

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Artisans Works with Kalava Crafts |

| Material | |

| Made of | Soft 100% Cotton |

| Instruction | |

| Note | - Two layered hand made cotton mask is a comfortable, reusable and easily washable. - Imperfections and variations in the product cannot be termed as defects, as these are intrinsic to the handmade process.These might slightly differ from as seen on digital screen. -For bulk order, please contact [email protected] |

| Restrictions | |

| COD - Option | Not Available |

| International Shipping | Not available |

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-234x234w.jpg)

-234x234h.jpg)