- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Gaatha

- Product Code: 1628-AP24-08

- Weight: 1,500.00g

- Dimensions: 88.00cm x 15.00cm x 15.00cm

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

9328006304 ( WhatsApp )

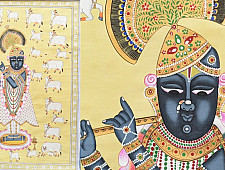

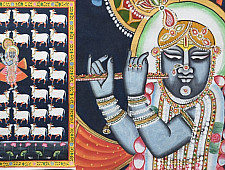

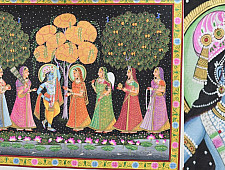

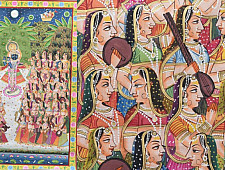

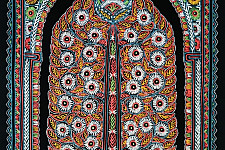

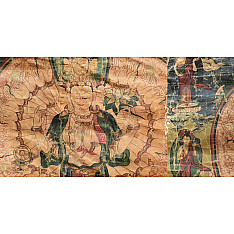

A work of art, matchless in splendour, which originated as an inspiration for meditation for the monks in the cold mountains of Tibet, shines all over the world in hues of golden and blue. Beautiful manifestations of the divine, the Thangka paintings help Tibetan Buddhist practitioners develop a close relationship with a meditational deity, assisting them in clearly visualizing particular images.

The awakened one, Lord Buddha, lived about 2600 years ago in India and taught the Holy Dharma to a large following; also instructed and inspired many artists. As monks spread Buddha’s teachings in India and beyond, they carried with them rolled up paintings, which served as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas. The Tibetan word “thang yig” meaning a written record, thus gave “Thangka” its name.

To establish Buddhism in Tibet, in the 7th century, the Tibetan king Songsten Gampo married the Chinese princess Kongjo, who brought scriptures of Lord Buddha’s Teachings, sculptures and paintings, and with artists who came with her, also introduced a Chinese style of painting in Thangka. Traditionally, a thangka was the combined result of a sacred human trio: a lama, a religious practitioner and a thangka artist. The practitioner, having sought the counsel of a qualified Buddhist lama, learned which deity image of the Tibetan pantheon was most beneficial for his or her spiritual practice. He or she then invited a thangka painter to his or her home and hosted the artist with the best possible hospitality for the duration of the painting process.

In order that the finished thangka be worthy of the practitioner’s heartfelt devotion, offering and meditation practice, the thangka painter generated a pure intention free of all selfish motives and undertook the task with a joyful mind. There was no discussion of price when the order was placed, and the thangka was not considered a mere commodity but as a living expression of enlightened energy. There are thousands of different deities in Tibetan Buddhism and each deity has geometric measures accurate, researched and written in ancient manuscripts. Not only the accuracy of the lines and the size of the images that have great symbolic importance, but also their colors, the position of the body and hands, the instruments appear and offerings given, guard symbolic values.

Thangka have developed in the northern Himalayan regions among the Lamas. Besides Lamas, Gurung and Tamang communities also make Thangka paintings. Thanka painting’s measurement, costumes, implementations and ornaments are all based on Indian style. The drawings of figures are based on Nepalese style and the background sceneries are based on Chinese style. Thus, the Thanka paintings are a unique and distinctive art.

The making of Thangka paintings is a painstaking procedure and involves repetition of many processes over and over again to achieve perfection.Usually cotton and more rarely silk; the canvas is stretched over a wooden frame using a cord that allows tension to be adjusted after the cloth has been sealed with a moist mixture of chalk and gesso. The surface is polished with a smooth stone or glass, until the underlying texture of the canvas is no longer apparent. This complex process of preparation of cloth takes between 14 to 20 days depending on local climatic conditions. Having studied the description of the image to be painted in a religious text and consulted a lama, the artist recites the sacred syllables of the Buddha or deity in question and begins to draw. The design for the painting is then drawn directly onto the taut surface using charcoal or pencil. Once the initial sketch is complete, the lines are redrawn in ink and the details are refined.

The colours are traditionally made from minerals as well as vegetable dyes, each collected from its source in different areas of Tibet, cleaned, ground, powered, crushed or cooked. Traditional paint brushes were made out of several different materials, such as, Nama grass for painting on rough surfaces; horse- tail hair for medium brushes, and for fine brushes, soft fur of animals or the very soft feathers of mountain songbirds were used. The handle of the brush is a slender piece of upward growing bamboo cut just above the joint. Nowadays Tibetan artists also use modern synthetic dyes, silver and gold as well as ready made brushes.

There is a definite, specific sequence to color application. The first step is the sky, and then all the blue areas like water, clothing etc. are filled in. The dark green landscape and all the dark green areas are next. This is followed by lighter colors and then finally white. After drying, the colors are scraped for a smooth finish. The artist then redraws and shades the figures and objects in minute detail using fine brushes. A considerable quantity of gold is used to highlight and give it its final glorious touches. Tiny pieces of gold are finely ground with water and marble or glass and glue is added. This process is repeated for days before gold is distilled and dissolved in water, glue and egg white to prepare a fine paste for application on the painting.

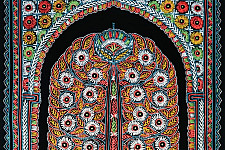

The most important moment of a thangka artist’s work is opening of the eyes of the image preceding which, the artist bathes and makes offerings to the Buddha. When the eyes have been painted, seed syllables and prayers are inscribed on the back of the thangka to awaken the image’s energy. The painting is later mounted in a silk brocade border. The practitioner takes his or her newly completed thangka to a highly realized Buddhist master who is able to “bring alive” the image on the thangka by infusing it with energy and beseeching the deity to open its eyes and look upon all sentient beings. The thangka, having now been properly consecrated, is a receptacle of wisdom. Over the centuries, it has been believed that many important Buddhist masters have intentionally taken rebirth as thangka painters, and if such an artist creates a thangka, the very mind of the artist naturally consecrates the image being painted.

Awareness about Tibetan art and culture has brought an increase in tourism and consequently, has led to the trend of commissioning Thangkas as pieces of art for personal possession. This emerging trend provides a means of livelihood to the artists along with conservation of the tradition, while promoting the art form for appreciation by a wider more global audience. by ~Anuj Kumar Sharma | Priya Shah | Pooja Khadkiwala

Read in detail here ~ Gaatha.org

| Returns and Exchange | |

| Note | ♦ The items in this category are non refundable and non exchangeable. ♦ These pieces are antique in their original form. The fabric is old, and the colors are imperfect in many places. |

| Material | |

| Made of | Cotton base and natural colours |

| Instruction | |

| About Sizes | Total- 28x48 Painting - 22x33 inch |

| Restrictions | |

| COD - Option | No Available |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-80x80h.jpg)

-80x80w.jpg)

-225x170w.jpg)

-225x170w.jpg)

-225x170w.jpg)

-225x170w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150h.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-234x234h.jpg)