Bengal has long been recognised as a region rich in art and craft traditions. These practices are deeply rooted in the social, cultural, and spiritual fabric of Bengal, evolving over centuries as part of everyday life rather than as isolated artistic pursuits. Through this continuous engagement with making, communities have developed a strong visual memory and a distinctive aesthetic sensibility.

In Bengal, material is never just material. Whatever artisans touch transforms into art. These craft traditions are not restricted to a single medium. Artisans have explored and mastered textiles, clay, metal, brass, wood, tree bark, and many other natural resources, adapting techniques across forms while maintaining a cohesive cultural identity.

Over time, the influence of British colonial aesthetics introduced new visual frameworks and institutional art education. Simultaneously, figures like Rabindranath Tagore played a significant role in reshaping artistic thought and society’s relationship with creativity. Through his vision of integrated art, education, and rural engagement, he contributed to a renewed dialogue between tradition and modernity, leaving a lasting impact on Bengal’s cultural landscape.

1. BALUCHARI SAREE

Baluchari sarees are exquisite handwoven silk sarees that originated in the 18th-century Baluchar, West Bengal and later perfected in Bishnupur (Bankura district). They are especially famous for their intricate woven designs and storytelling motifs which depict scenes from Ramayana, Mahabharata, royal processions, court scenes, temple art, animals, and mythological figures on the pallu(the decorative end drape of the saree). They use a jacquard extra-weft technique where colored silk threads are woven into detailed patterns which is a highly skilled and time-intensive method. Authentic Baluchari sarees are typically made of pure mulberry silk (Bishnupuri silk), giving them a luxurious drape and feel. In 2011, Baluchari sarees received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in India, protecting their authenticity and heritage.

2. JAMDANI

Jamdani is a traditional handwoven textile from Bengal, known for its airy cotton fabric and delicate woven motifs. Historically produced in Dhaka, the craft continues today in West Bengal as well. Originating during the Mughal era, it was once worn by royalty for its sheer fineness. The craft uses an extra-weft technique, where motifs are woven directly into the fabric by hand. These designs appear to float on the surface, giving Jamdani its signature lightness.Common motifs include florals, paisleys, vines, and geometric forms. Traditional Jamdanis were woven in soft whites and pastels. Modern versions explore colour, silk blends, and contemporary patterns. Bengal Jamdani holds a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in India. Often called “woven air,” Jamdani represents slow, patient craftsmanship.

3. SHOLA PITH CRAFT

Shola Pith craft is a traditional art form from West Bengal, made from the soft, sponge-like stem of the shola plant. Often called “Bengal’s ivory”, shola is naturally white, light, and delicate. The craft is closely associated with Bengali rituals and ceremonies, especially weddings and festivals. Artisans hand-carve the pith using simple tools to create intricate forms. Common objects include topors (bridal headgear), durga idols’ decorations, flowers, and ornamental figures. Shola work plays a major role in Durga Puja pandals and iconography. This craft in today’s date is still practised in Murshidabad, Bardhaman, and Medinipur. Despite its fragile appearance, Shola Pith holds deep cultural significance. The craft reflects Bengal’s tradition of lightness, purity, and symbolism.

4. BANKURA TERRACOTTA

Bankura terracotta is a centuries-old clay craft tradition from Bankura district, West Bengal, particularly practised around Bishnupur. It developed under the patronage of the Malla kings between the 16th–18th centuries, especially for temple architecture. Artisans use locally available laterite-rich clay, which gives the craft its distinctive warm red colour. The clay is hand-moulded or wheel-thrown, sun-dried, and then kiln-fired at high temperatures. Bankura terracotta is deeply narrative, depicting mythological scenes from Ramayana or Mahabharata episodes, folk deities, musicians, animals, and village life. The most iconic form is the Bankura horse, originally used as a ritual offering and now a cultural symbol of Bengal. Terracotta panels extensively decorate temples like the Rasmancha and Jor Bangla temples of Bishnupur. Bankura Terracotta Craft does hold a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, recognised as a traditional terracotta art of Bankura district. Today, it extends beyond ritual use into sculptures, decor, and contemporary art objects, while still retaining its folk soul.

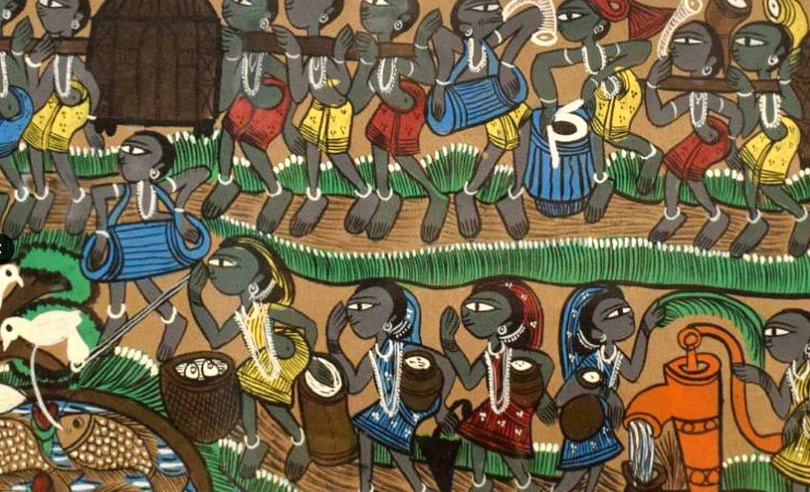

5. PATTACHITRA

Pattachitra(also called Patua art) is a traditional narrative painting style from West Bengal, practiced for centuries. The art form combines visual storytelling, music, and oral tradition. Paintings are made on cloth or paper prepared with natural adhesives. Artists, known as patuas, paint long scrolls or single-frame artworks. Each scroll tells a story which is often from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Mangal Kavyas, and folk legends. Traditionally, patuas travel from village to village, singing pater gaan while revealing the images panel by panel. Colours are derived from natural sources like stones, leaves, flowers, and soot. The style is marked by bold lines, flat colours, and expressive figures. The craft is still preserved in parts of Medinipur, Birbhum, Bankura, and Purulia till date. Pattachitra in Bengal has also received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag as a recognised craft form from the region. Today, Pattachitra also addresses contemporary themes, blending tradition with modern narratives.

6. KALIGHAT PAINTING

Kalighat is a painting of the 19th century Bengal. The painting was developed near Kalimandir in the Kalighat region of Kolkata. At that time, the pilgrims of these paintings were bought as a memorial. During the period, the painting became a distinct genre of Indian painting. The film was a film of Hindu deities and other mythological characters and contemporary events. The paintings often critiqued colonial society, babu culture, and moral hypocrisy. Artists used mill-made paper and water-based pigments, reflecting colonial-era material shifts. The style is marked by strong sweeping brush lines, flat colour blocks, and sparse backgrounds. Production was workshop-based, allowing faster output for temple markets. By the late 19th century, cheap chromolithographs reduced demand, leading to decline. Today, original works are preserved in museums like the Indian Museum (Kolkata) and the Victoria & Albert Museum (London). Contemporary artists and institutions in Kolkata continue to revive the aesthetic. Kalighat painting remains a key moment in Indian art history, bridging folk practice and early modern visual culture.

7. GARAD AND TANT SAREE

Garad and Tant sarees are foundational cotton handlooms of West Bengal, shaped by ritual, climate, and craft traditions. Both are woven by hereditary weaver communities using traditional pit looms. Garad sarees originated as ceremonial textiles, woven from unbleached, undyed cotton considered ritually pure. The signature red border and pallu are woven on the loom using dyed yarns, symbolising auspiciousness. Garad weaving developed around temple towns and ritual centres of Bengal. The fabric is tightly woven, durable, and meant for sacred occasions. Tant sarees evolved as everyday wear suited to Bengal’s hot and humid climate. They are woven using fine cotton yarns that create light, breathable fabrics. Yarns are dyed before weaving, allowing vibrant colours and sharp borders. Motifs drawn from folk art, geometry, and Jamdani-inspired techniques are seen. Tant weaving clusters such as Tantubay and Basaks are found across Shantipur, Phulia, and Dhaniakhali. Dhaniakhali Tant holds a Geographical Indication (GI) tag, recognising its unique weave and artisan heritage.8. CHHAU MASK

Chhau masks are traditional handcrafted masks used in the Purulia Chhau dance of West Bengal. They are an essential element of this martial-ritual dance form, performed during festivals like Chaitra Parva. The craft is primarily practised in Charida village (Purulia district), known as the mask-makers’ hub. Artisans shape the base using clay moulds layered with paper and cloth. After drying, the mask is sun-hardened, refined, and coated with chalk paste. It is then painted in vivid colours and decorated with foil, feathers, beads, and fabric. Each mask represents specific characters from epics, Puranas, or local folklore. Facial expressions are exaggerated to convey emotion from a distance. The craft is traditionally sustained by artisan families linked to performer communities. Chhau dance itself is recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage (2010). The Purulia Chhau mask (made in Charida village, Purulia district, West Bengal) was officially registered with a GI tag in 2018, recognising its unique regional craftsmanship and cultural identity. The masks are also sold as decorative objects beyond performance contexts. Today, Charida remains the principal centre where this living craft continues to thrive.

9. KRISHNA NAGAR DOLLS

Krishnanagar dolls are handcrafted clay figures from Krishnanagar, Nadia district, West Bengal. The craft dates back to the 18th century, flourishing under royal patronage. Artisans use fine alluvial clay from the Bhagirathi river basin. Each figure is first modelled in clay and then cast using moulds. Details like facial expressions, jewellery, and clothing are shaped by hand. The dolls are known for their lifelike realism and emotional expression. Themes range from mythology and folk life to colonial-era figures and social scenes. After shaping, the dolls are sun-dried and kiln-fired. They are then hand-painted with natural and mineral-based colours. You can see Krishnanagar clay dolls being made today in Ghurni, Krishnanagar, where artisan families still run workshops. In 2017, Krishnanagar Clay Dolls received a Geographical Indication (GI) tag. Today, they remain a living symbol of Bengal’s sculptural and storytelling heritage.

10. DHOKRA

Dhokra is an ancient metal casting tradition practiced in parts of West Bengal, especially in Bankura, Purulia, Bardhaman, and Medinipur. This sort of metal casting has been used in India for over 4,000 years and is still in practise. One of the earliest known lost wax artifacts is the dancing girl of Mohenjo-daro. The product of dhokra artisans are in great demand in domestic and foreign markets because of primitive simplicity, enchanting folk motifs and forceful form. Dhokra horses, elephants, peacocks, owls, religious images, measuring bowls, and lamp caskets etc., are highly appreciated. The aesthetic is marked by elongated forms, coiled wire patterns, and textured surfaces. Artisans create a clay core, layer it with beeswax to form intricate patterns, and cover it with clay moulds. Molten brass is then poured into the mould after the wax is melted out. Each piece is unique, as the mould must be broken to retrieve the object. In Bengal, the craft evolved through forest-based and rural economies. Dhokra of Bankura and Bardhaman received a GI tag in 2018, recognising its regional identity. Today, it stands as a living example of continuity between ancient metallurgy and contemporary tribal craft practice

Leave a Comment