- Availability: 1

- Made & Mkt by: Kala Aur Katha

- Product Code: 4008-PS-21

- Weight: 400.00g

The typical dispatch time is 2-3 days; however, in special cases, it may take longer. Please refer to the product details section for specific timelines. Once dispatched, we will share the tracking details with you.

For returns, you can file a request within 24 hours of receiving the product. If the package is damaged, please make a video while unboxing and share images of the damaged item along with your return request.

9328006304 ( WhatsApp )

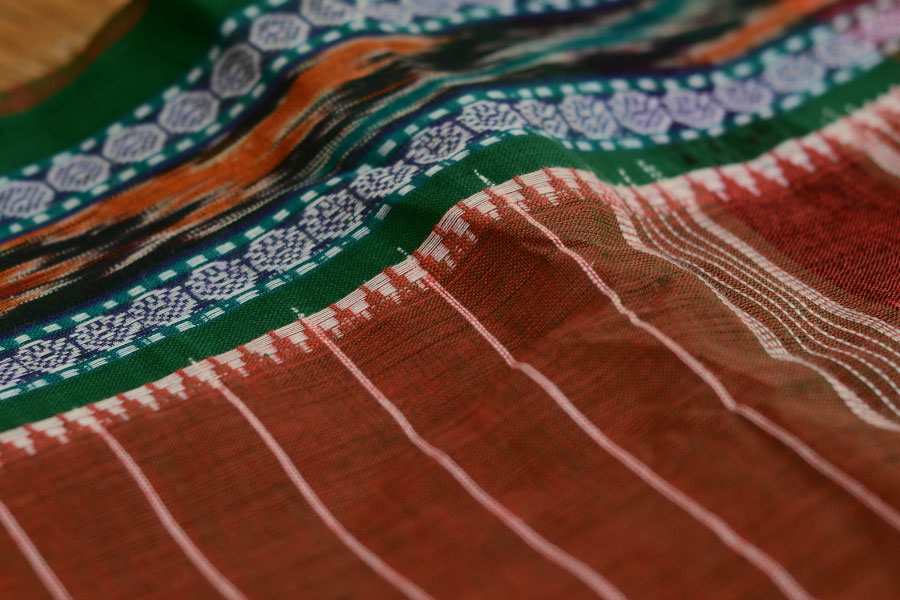

In early 16th century when Vaishnav cult was flourishing, a group of weavers from Bengal migrated to Orissa with Chaitnya Prabhu. This resulted in blending of Bengal weaving with patterns from Orissa, creating a beautiful combination of textures and drapery styles. Symbolic Temple and Rudraksha patterns in thread work along the border from Orissa hand woven textiles brought a new dimension to textile techniques of Bengal. Today, Jagatsingpur district in the eastern belt is the only place in Orissa where weavers are still engaged in weaving excellent quality of single count cotton fabrics called ‘Suta luga’ (cotton weaves), celebrating eight hundred years of weaving tradition kept alive by the devotees of Chaitnya prabhu.

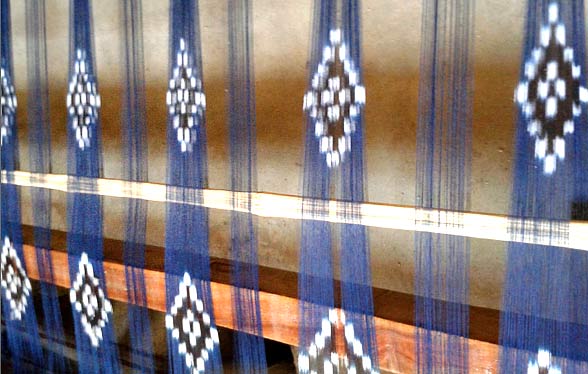

Organizations like Kala Aur Katha work together with the weavers of Jagatsigpur to bring us their skills and for required design interventions that can help them make a place in the contemporary market. Making of bright and colorful single cotton saris enhanced with ikat, extra weft thread work and dobby borders in ‘Temple’ and ‘Rudraksha’ motifs is one such initiative. Extra weft threads are also called as supplementary threads and are inserted in horizontal direction. They are woven along with the main weft yarn. Malli (Jasmine), Patra (leaf), Mayura (peacock), Padma (lotus) and Tribhuja (triangle) are the patterns from nature usually woven in the saris using extra weft thread. Dobby patterns are made with supplementary threads running vertically across the borders of the sari. Weavers also experiment with basic ikat techniques. Usually dyed ikat strands from neighboring Nuapatna area are used in dhadi (borders) and also in the kani (Pallu) to enhance the elegance of single count cotton sari.

The process of single count untwisted cotton is tedious. Usually 40s, 60s and 80s single count cotton and 2/80s mercerized cotton is used in the sari. The unbleached threads or yarns are scoured, bleached and dyed in desired color. It is soaked in rice starch prior to warping and after warping. The warp is stretched in open space and starched manually using wide broom like tool by hand. The process of winding, drafting, denting, weaving and spinning weft thread is an ongoing three week process in the making of sari.

While sitting on loom the weaver reads the graph pattern and inserts extra weft threads skillfully one by one to create the desired pattern. Men and women both are engaged in the entire process of weaving. Men and women both make the warp and weft of ‘Suta luga’.

Unfortunately, the Super cyclone in 1999 erased houses and families of hundreds of weavers and the tradition of weaving to a large extent. After the cyclone very few weavers continued with the weaving tradition. A shift in the local market and need for locally produced fabric also resulted in shifting livelihood options. The weavers are getting old now and in some villages the craft is berating its last. In addition to such social issues, with age weaving finer count sari is a challenge, leaving choosing coarser yarn as the only option.

Some weavers in their late sixties choose to weave because there is no alternate livelihood for sustenance. Younger generations are not interested in weaving due to inadequate wages. Currently, some weavers live on farming and weaving simultaneously to meet the basic amenities of household requirements.

Amidst such loss of interest and skills Lobhabhati Sahoo, a proud mother of five year old son and a weaver is one of the few remaining weavers of the town. Lobhabati is depended only on weaving for sustaining her family and bears the cost of her son’s education with it. She weaves and runs her family singlehandedly. A hand woven Suta Luga, cotton weave from Jagatsigpur supports several such families. Story and Images by ~ Pankaja Sethi, Kala Aur Katha

| Craftsmen | |

| Made by | Artisans working with Kala aur Katha |

| Details | |

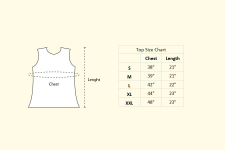

| Product details | A full length saree |

| Material | |

| Made of | 100 % cotton |

| Instruction | |

| Note | -Imperfections and variations in the product cannot be termed as defects, as these are intrinsic to the handmade process. |

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-225x150w.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)

-234x234.jpg)